Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Australia Correspondent

With a bright pink tweezers in hand, Emma Teni subtly struggles a large and long -legged spider in a small plastic pot.

“He poses,” shuns the Spider keeper as he comes up on his hind legs. It is exactly what she is trying to achieve – that way she can suck the poison out of his teeth with the help of a small pipette.

Emma works from a small office that is known as the Spider Milking Room. On a typical day she melts -or does the poison -80 of this Sydney -ikrechter -Web spiders.

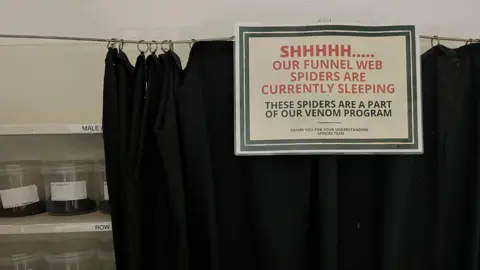

On three of the four walls, from floor to ceiling boards are full of spiny plots, with a black curtain pulled to keep them calm.

The remaining wall is actually a window. As a result, a small child stares, both fascinated and shocked, while Mrs. Teni works. They know little that the palm -large spider she uses could kill them within a few minutes.

“Sydney Funnel webs are perhaps the most deadly spider in the world,” says Emma soberly.

Australia is famous full of such deadly animals -and this room in the Australian Reptile Park plays a crucial role in a government -Antvenom program, which saves lives on a continent where it often makes you kill everything you want to kill.

While the fastest absorbed death of a Sydney -ikrechter -Web Spider was a toddler after 13 minutes, the average is closer to 76 minutes -and first aid gives you an even better chance to survive.

The AntIvenom program here in the Australian Reptile Park is successful that nobody was killed by one since it started in 1981.

However, the schedule depends on members of the public, or catching the spiders or collecting their egg bags.

In a van plastered with a gigantic crocodile sticker, the team of Mrs. Teni drives every week in the most famous city in Australia and picks up Sydney-Trechter webs that have been handed in on drop-off points such as local veterinary practices.

There are two reasons why these spiders are so dangerous, she explains: not only is their poison extremely powerful, but they also live exclusively in a densely populated area where they are more likely to meet people.

Handyman Charlie Simpson is such a person. He moved to his first home with his girlfriend a few months ago and the Keen Gardener has already found two Sydney-Trichter webs. He took the second spider to the vet, where Mrs. Teni picked him up shortly afterwards.

“I was wearing gloves at the time, but realistically I should have learned gloves because their teeth are so big and strong,” says the 26-year-old.

“I (I thought) that I can catch it better because I was always told that you have to take the intention to take them back to be milked because it is so critical.”

“This is my fear of spiders,” he jokes.

While Mrs. Teni charges an Arachnid that was delivered to her in a Vegemite pot, she emphasizes that her team does not tell Australians to look for the spiders and “to danger themselves”.

They rather ask that if someone comes across one, they capture it safely instead of killing it.

“Saying that this is the world’s most deadly spider and then (asking the audience to catch it) and bring it to us, sounds contrainly,” she says.

“(But) that spider there now, thanks to Charlie, will … effectively save someone’s life.”

All spiders that her team collects are returned to the Australian Reptile Park where they are cataloged, sorted by sex and stored.

All women who are deposited are taken into account for a breeding program, which helps to replenish the number of spiders donated by the public.

In the meantime, the men, who are six to seven times more toxic than the women, are used for the AntIvenom program and milked every two weeks, Emma explains.

The pipette she uses to remove the poison from the teeth is attached to a suction hose – crucial for collecting as much poison as possible, because each spider only offers small quantities.

Although a few drops are enough to kill, scientists have to milk 200 of these spiders to have enough to fill one bottle of Antivvenom.

A marine biologist through training EMMA never expected to spend her days milking spiders. She even started working with seals.

But now she wouldn’t have it in any other way. Emma loves all things and goes under different nicknames – Spider Girl, Spider Mama, even “Weirdo”, as her daughter calls her.

Friends, family and neighbors rely on her because of her knowledge of the scary crawlies of Australia.

“Some girls come home for flowers in front of their door,” Emma jokes. “For me it is not unusual to get home at a spider in a pot.”

Spiders represent only one small part of what the Australian Reptile Park does. It also offers snake venom to the government since the 1950s.

According to the World Health Organization, no fewer than 140,000 people die around the world every year from snake bites, and three times that many remain disabled.

In Australia, however, those figures are much lower: every year between one and four people, thanks to the successful AntiVenom program.

Billy Collett, the operations manager of the park, removes a King Brown Snake from his storage cupboard and brings it to the table for him.

With his bare hands, he secures his head and puts his jaws over a shot glass covered with a household film.

“They are very delegated to bite, but as soon as they go, you just see it flowing out of the teeth,” says MR Collett, while yellow gif drips to the bottom.

“That is enough to kill us all in the room five times – maybe more.”

Then he switches in a more reassuring tone: “They are not looking for people to bite. We are too big for them to eat; they don’t want to waste their poison on us. They just want to be left alone.”

“To be bitten by a toxic snake, you really have to annoy it, provoke it,” he adds, and notes that bites often occur when someone tries to kill one of the reptiles.

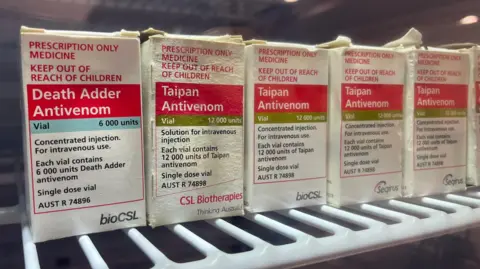

There is a fridge in the corner of the room where the raw gif MR Collett collects is stored. It’s full of bottles with the “Death Adder”, “Taipan”, “Tiger Snake” and “Eastern Brown”.

The last of these is the second most toxic snake in the world, and the one who is most likely to bite you here, in Australia.

This poison is freezed and sent to CSL Seqirus, a laboratory in Melbourne, where it has turned into a antidote in a process that can last up to 18 months.

The first step is to produce what is known as hyper-immune plasma. In the case of snakes, controlled doses of the poison are injected into horses because they are larger animals with a strong immune system.

The poison of Sydney Funnel-Web Spiders goes into rabbits, which are immune to the toxins. The animals are injected with increasing doses to build their antibodies. In some cases only that step can take almost a year.

The supercharged plasma of the animal is removed from the blood and then the antibodies are isolated from the plasma before being bottled, ready to be administered.

CSL Seqirus makes 7,000 bottles a year – including hose, spider, stone fish and box of jellyfish AntIndenoms – and they are valid for 36 months. The challenge is to ensure that everyone who needs it has stocks.

“It’s a huge enterprise,” says Dr. Jules Bayliss, who leads the AntIvenom development team at CSL Seqirus.

“First and foremost we want to see them in large rural and remote areas in which these beings are likely to be.”

Falls are distributed, depending on the species in every area. Taipans, for example, are in the northern parts of Australia, so there is no need for their anti -venom in Tasmania.

AntIndom is also given to the Royal Flying Doctors, who have access to some of the most remote communities in the country, as well as Australian naval and cargo ships for sailors with a risk of sea-courses.

Papua -New Guinea also receives around 600 bottles per year. The country was once connected to Australia through a Landbrug and shares many of the same snake species, so the Australian government gives the AntiVenom free – snake diplomacy, if you want.

“To be honest, we probably have the most impact in Papua -Guinea, even more than Australia, because of the number of snake bites and killing they have,” says CSL Seqirus -Executive Chris Larkin. To date, they think they have saved 2,000 lives.

Back in the park, Mr. Collett jokes about the nickname of “Danger Noodles” who is sometimes given to his serpentine colleagues – a classic Australian feature of making something that gives so many visitors nightmares.

However, MR Collett is clear: these animals are not allowed to scare people to visit.

“Snakes not only sail through the streets that attack British – it doesn’t work that way,” he jokes.

“If you are bitten by a snake, Australia is the best place – we have the best antivenom. It’s free. The treatment is unreal.”