Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

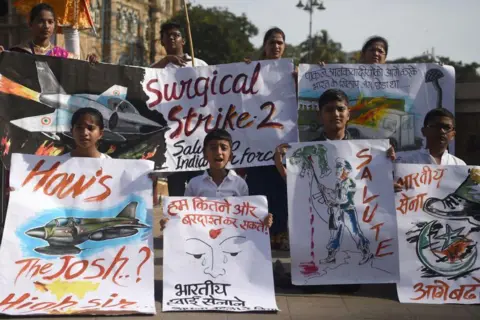

Getty images

Getty imagesLast week’s deadly militant attack in Pahalgam in Kashmir, rated by the Indian, who claimed 26 civilian lives, has a grim sense of Déjà Vu again for India’s security forces and diplomats.

This is well -known land. In 2016, after 19 Indian soldiers were killed in UriIndia launched “surgical strikes” over the line of control – the de facto boundary between India and Pakistan – focused on militant bases.

In 2019, the Pulwama -bombingso that 40 Indian paramilitarian staff were asked to death, Air strikes deep in Balakot – The first such action in Pakistan since 1971 – Relaxed retaliation attacks and an air dog fight.

And before that, the horrible 2008 Mumbai -attacks – A 60 -hour siege on hotels, a train station and a Jewish center – claimed 166 lives.

Every time India has held militant groups based in Pakistan who are responsible for the attacks and accused the Islamabad of tacit support of them – an indictment that Pakistan has consistently denied.

Since 2016, and especially after the 2019 air strikes, the threshold for escalation has been dramatically shifted. Cross -border and air strikes of India have become the new standard, which causes retribution from Pakistan. This has further intensified an already volatile situation.

Again, experts say that India is running the cord between escalation and restraint – a fragile response and deterrence. A person who understands this recurring cycle is Ajay Bisaria, the former High Commissioner of India in Pakistan during the Pulwama attack, who conquered his aftermath in his memoirs, anger control: the troubled diplomatic relationship between India and Pakistan.

Getty images

Getty images“There are striking parallels between the aftermath of the bomb attack on Pulwama and the murders in Pahalgam,” Mr. Bisaria told me on Thursday 10 days after the last attack.

Yet he notes, Pahalgam marks a shift. In contrast to Pulwama and Uri, who focused on security forces, this attack met citizens – tourists from all over India – who evoke memories of Mumbai’s attacks from 2008. “This attack carries elements of Pulwama, but much more of Mumbai,” he explains.

“We are again in a conflict situation and the story unfolds in almost the same way,” says Bisaria.

A week after the last attack, Delhi quickly moved with retaliation measures: closing the main border transition, suspending a key distribution of the water distribution, the expulsion of diplomats and stopping most Visa for Pakistani subjects – those days were given to leave. Troops on both sides have exchanged intermittent small arms fire across the border in recent days.

Delhi has also blocked all Pakistani aircraft – commercial and military – from his airspace, reflected the earlier step of Islamabad. Pakistan took revenge on his own visa suspensions and has suspended a peace treaty from 1972 with India. (Kashmir, fully claimed by both India and Pakistan, but each is administered in parts, has been a flash point between the two nuclear arming countries since their partition wall in 1947.)

Ajay Bisaria

Ajay BisariaIn his memoirs, Mr. Bisaria tells India’s reaction after the Pulwama attack on February 14, 2019.

He was called to Delhi the following morning, while the government quickly moved to stop trade – With Pakistan’s most beneficial nation status withdrawalgranted in 1996. In the following days, the Cabinet Committee for Security (CCS) imposed a customized customs duties of 200% of Pakistani goods, which means that the import was effectively terminated and the trade on the land border near Wagah was suspended.

Mr. Bisaria noted that a broader series of measures was also proposed to scale the involvement in Pakistan, most of which were subsequently implemented.

They include suspending a cross -border train that is known as the Samjhauta Express, and a bus service that connects Delhi and Lahore; Postponing conversations between border guards on both sides and negotiations on the historical Kartarpur -Gang To one of the holiest shrines of Sikhism, stopping visa output, stops cross border, forbidding Indian trips to Pakistan and suspending flights between the two countries.

“How difficult it was to build trust, I thought. And how easy it was to break it,” writes Mr. Bisaria.

“All measures for building trust planned, negotiated and implemented in this difficult relationship can be cut off on a yellow notebook within a few minutes.”

The strength of the Indian High Commission in Islamabad was reduced from 110 to 55 after Pulwama. (It is now 30 after the Pahalgam attack.) India also launched a diplomatic offensive.

A day after the attack, Minister of Foreign Affairs Vijay Gokhale informed envoys from 25 countries-including the US, the UK, China, Russia and France-over the role of Jaish-E-Mohammad (JEM), the Pakistan-based militant group behind the bombing and Pakistan accused of terrorism as a state policy. Jem, designated a terrorist organization by India, the UN, the UK and the US, had claimed responsibility For the bombing.

AFP

AFPIndia’s diplomatic offensive took place on 25 February, 10 days after the attack, insistently on Jem Chief Masood AzharThe designation as a terrorist by the UN Sanctions Committee and inclusion on the ‘autonomous terror list’ of the EU.

While there was busy the Indus Waters Treaty – A key agreement for sharing river water – India chose to remember data that goes beyond treaty obligations, writes Mr Bisaria. A total of 48 bilateral agreements were assessed for possible suspension. An All-Party meeting was convened in Delhi, which resulted in a unanimous resolution.

At the same time, communication channels were openly inclusive of the hotline between the directors of the two countries-general of military operations (DGMO), an important link for military-to-military contact, as well as both high committees. In 2019, like now, Pakistan said the attack one “False Flag editing”.

Really bad this time A performance in Kashmir saw the arrest of more than 80 “above -ground employees” – local supporters who may have offered logistical help, shelter and intelligence to militants of the group established in Pakistan. Rajnath Singh, the then Minister of the Interior, visited Jammu and Kashmir, and files for the attack and suspected perpetrators were prepared.

In a meeting with the Minister of Foreign Affairs Sushma Swaraj, Mr. Bisaria told her that “that the diplomatic options of India was limited in dealing with a terrorist attack of this nature”.

“She gave me the impression that a tough action was around the corner, after which I would expect the role of diplomacy to expand,” writes Mr. Bisaria.

On 26 February, Indian Airstikes – the first on the other side of the international border since 1971 – aimed the training camp of Jem in Balakot.

Six hours later, the Indian Foreign Minister announced that the strikes had killed “a very large number of” militants and commanders. Pakistan quickly denied the claim. More meetings at a high level followed in Delhi.

AFP

AFPThe crisis escalated dramatically the next morning, 27 February, when Pakistan launched retaliation attacks.

In the subsequent dog fight, an Indian fighter jet was shot, and the pilot, wing commander Abhinandan Varthaman, shot and landed in Pakistan-assessed Kashmir. Caught by Pakistani troops, his detention caused a wave of national concern in enemy territory and further increased tensions between the two nuclear armed neighbors.

Mr. Bisaria writes India activated several diplomatic channels, with the American and British envoys that urge urgent Islamabad. The Indian message was “any attempt by Pakistan to escalate the situation or to damage the pilot would lead to escalation by India.”

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan announced the release of the pilot on 28 February, with the transfer that takes place on March 1 Under Prisoner of War Protocol. Pakistan presented the move as a “goodwill gesture” focused on de-escalating tensions.

By March 5, with the dust that settled from Pulwama, Balakot and the return of the pilot, the political temperature of India had cooled. The Cabinet Committee for Security decided to send the high commissioner of India back to Pakistan, which indicates a shift to diplomacy.

“I arrived in Islamabad on 10 March, 22 days after departure in the aftermath of Pulwama. The most serious military exchange since Kargil had his course in less than a month,” writes Mr. Bisaria,

“India was willing to give old -fashioned diplomacy another chance …. this, in which India has achieved a strategic and military goal and Pakistan had demanded an idea of the victory for his domestic public.”

AFP

AFPMr. Bisaria described it as a “testing and fascinating time” to be a diplomat. This time, he notes, the most important difference is that the goals were Indian citizens, and the attack took place “ironically, when the situation in Kashmir was dramatically improved”.

He regards escalation as inevitable, but notes that there is also a “de-escalation instinct in addition to the escalation instinct”. When the Cabinet Committee for Security (CCS) meets during such conflicts, he says, their decisions weighs the economic impact of the conflict and look for measures that harm Pakistan without causing a recoil against India.

“The body language and optics are similar (this time),” he says, but emphasizes what he sees as the most important move: the threat of India to cancel the Indus Waters treaty. “If India deals with this, it would have serious consequences for Pakistan in the long term.”

“Don’t forget that we are still in the middle of a crisis,” says Mr. Bisaria. “We haven’t seen any kinetic (military) action yet.”