Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC World Service

Phil Caller

Phil CallerNestled in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan is the picturesque village of Sergele.

For generations, villagers have had the living growing pomegranates, almonds and peaches and foraging in the surrounding forests for wild fruit and herbs.

But Sergele, 16 km (10 miles) from the border with Turkey, is increasingly surrounded by Turkish military bases, which are littered over the slopes.

One, halfway through the western ridge, looms over the village, while another in the east is under construction.

In the past two years, at least seven have been built here, including one by a small dam that controls the water supply of Sergele, which is put on the limits for villagers.

“This is 100% a form of occupation of Kurdish (Iraqi Kurdistan) countries,” says farmer Sherwan Sherwan Sergeli, 50, who has lost access to a part of his country.

“The Turks ruined it.”

Phil Caller

Phil CallerSergele is now in danger of being dragged into what is known locally as the “forbidden zone” -a large strip of land in North Iraq struck by the war of Turkey with the Kurdish militant group De PKK, which launched an uprising in South Turkey in 1984.

The forbidden zone includes almost the entire length of the Iraqi border with Turkey and is deep in places up to 40 km (25 miles).

Community Peacemaker Teams, a human rights group based in Iraqi Kurdistan, says that hundreds of citizens were killed by drone and air strikes in and around the forbidden zone. According to a parliamentary report from Kurdistan from 2020, thousands were forced to have forced their country and were emptied entire villages due to the conflict.

Sergele is now effective on the front line of Turkey’s war with the PKK.

When the BBC World Service Eye Investigations team visited the area, Turkish aircraft pulled the mountains around the village to eradicate PKK militants, who have long been working from caves and tunnels in Noord -Irak.

Much of the country around Sergele was burned by shelling.

“The more bases they set up, the worse it gets for us,” says Sherwan.

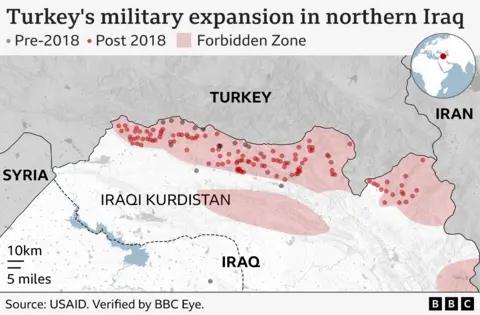

In recent years, Turkey has been rapidly growing its military presence in the forbidden zone, but so far the scale of this expansion was not publicly known.

With the help of satellite images assessed by experts and confirmed with on-the-ground report and open-source content, the BBC discovered that from December 2024 the Turkish army had built at least 136 permanent military installations in Northern Iraq.

Due to its enormous network of military bases, Turkey now has de facto control over more than 2,000 square km (772 square miles) Iraqi country, according to the analysis of the BBC.

Satellite images also reveal that the Turkish army has built at least 660 km (410 miles) roads that connect its facilities. These delivery routes have resulted in deforestation and have left a permanent print on the mountains of the region.

Although some of the bases date from the nineties, 89% have been built since 2018, after which Turkey began to considerably expand its military presence in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Turkish government did not respond to the requests of the BBC for interviews, but has maintained that its military bases are needed to reduce the PKK, which is designated by Ankara and a number of Western countries, including the UK.

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe capital of the Subdistrict of Kani Masi, which is only 4 km (2.5 miles) of the Iraqi-Turkish border and of which parts are within the forbidden zone, can offer a glimpse into the future of Sergele.

Once famous for its apple production, there are few residents here now.

Farmer Salam Saeed, whose country is in the shade of a large Turkish base, has not been able to cultivate vineyard in the last three years.

“The moment you arrive here, you will float a drone over you,” he says the BBC.

“They will shoot you if you stay.”

The Turkish army established here for the first time in the 1990s and has since consolidated its presence.

The most important military base, with concrete explosion walls, watch and communication towers and space for armored personnel carriers to enter, much more is developed than the smaller outdoor posts around Sergele.

Salam believes, like some other locals, that Turkey eventually wants to claim territory as his own.

“They just want us to leave these areas,” he adds.

Phil Caller

Phil CallerIn the neighborhood of Kani Masi, the BBC saw first hand how Turkish troops effectively pushed back the Iraqi border guard, who is responsible for the protection of the international borders of Iraq.

At various locations, the border guards who manage positions well on Iraqi territory, directly opposite Turkish troops, were unable to go straight to the border and possibly risk a collision.

“The messages you see are Turkish posts,” says General Farhad Mahmoud, pointing to a ridge just over a valley, about 10 km (6 miles) within the Iraqi territory.

But “we cannot reach the border to know the number of messages,” he adds.

The military expansion of Turkey in Iraqi Kurdistan – fed by his rise as a drone power and growing defense budget – is seen as part of a broader shift from foreign policy to greater interventionism in the region.

Just like its activities in Iraq, Turkey has also tried to establish a buffer zone along the border with Syria to contain Syrian armed groups connected to the PKK.

In public, the government of Iraq has condemned the military presence of Turkey in the country. But behind closed doors it has part of the requirements of Ankara.

In 2024, the two parties signed a memorandum of understanding to fight the PKK together.

But the document, obtained by the BBC, did not restrict Turkish troops in Iraq.

Iraq depends on Turkey for trade, investments and water safety, while broken internal politics has further undermined the government to take a strong position.

The national government of Iraq did not respond to the BBC requests for comments.

In the meantime, the rulers of the semi-autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan have a close relationship with Ankara on the basis of mutual interests and have often triggered civil damage because of Turkey’s military action.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), an arch enemy of the PKK, dominates the regional government of Kurdistan (KRG) and has been in charge since 2005, when the Constitution of Iraq granted the Semi-Autonomous status region.

The narrow ties of the KDP with Turkey have contributed to the economic success of the region and have strengthened its position, both against its regional political rivals and with the Iraqi government in Baghdad, which roughs for greater autonomy.

Hoshyar Zebari, a senior member of the Politburo of the KDP, tried to blame the PKK for the presence of Turkey in Iraqi Kurdistan.

“They (the Turkish army) don’t harm our people,” he told the BBC.

“They don’t hold them. They don’t interfere with them to do their business. Their focus, their only goal is the PKK.”

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe conflict does not show any signs of ending, despite the fact that the long -term leader of the PKK Abdulla Ocalan calls for his hunters in February to lay and defeat weapons.

Turkey has continued to save goals in Iraqi Kurdistan, while last month the PKK claimed the responsibility for downing a Turkish drone.

And although violent incidents in Turkey have decreased since 2016, according to a count of the NGO Crisis Group, those in Iraq have enriched, where citizens live on the border region who are confronted with a growing risk of death and displacement.

One of the killed was the 24-year-old Alan Ismail, a phase-four cancer patient affected by an air raid in August 2023 while on a trip to the mountains with his cousin, Hashem Shaker,.

The Turkish army has denied that that day is performing a strike, but a police report seen by the BBC attributes the incident to a Turkish drone.

When Hashem filed a complaint in a local court about the attack, he was held by Kurdish security forces and held on for eight months on suspicion of supporting the PKK – an accusation that he and his family deny.

“It destroyed us. It’s like killing the whole family,” says Ismail Chichu, Alan’s father.

“They (the Turks) have no right to kill people in their own country on their own country.”

The Ministry of Defense of Turkey did not respond to the requests of the BBC for comments. It has previously told the media that the Turkish forces follow international law, and that they only focus on terrorists in the planning and implementation of their activities, while causing citizens to harm citizens.

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe BBC has seen that documents suggest that Kurdish authorities may have acted to help Turkey to avoid the accountability for civilian casualties.

Seen confidential articles seen by the BBC show that a Kurdish court concluded the investigation into the murder of Alan and say that the perpetrator was unknown.

And his death certificate – published by Kurdish authorities and seen by the BBC – says he died due to “explosive fragments”.

Not mentioning when victims of air strikes died as a result of violence, instead of an accident, makes it difficult for families to look for righteousness and compensation, to which they are entitled under both Iraqi and Kurdish law.

“In most death certificates, they only wrote ‘Infijar’, which means explosion,” says Kamaran Othman of Community Peacemaker teams.

“It can be all that explodes.

“I think the Kurdish regional government does not want to make Turkey responsible for what they do here.”

The KRG said that it acknowledged the “tragic loss of citizens as a result of military confrontation between the PKK and Turkish army in the region”.

It added that “a number of victims” were documented as “civil martyrs”, which means that they were wrongly killed and are entitled to compensation.

Almost two years after Alan was murdered, his family still waits, if not compensation, at least for recognition of the KRG.

“They can at least send their participation – we don’t need their compensation,” says Ismail.

“If something is gone, it has disappeared forever.”