Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Music correspondent

Getty images

Getty imagesThirty -five seconds. That is all the time that you can change the set to Eurovision.

Thirty -five seconds to get one set of artists off the stage and put the next in the right place.

Thirty -five seconds to ensure that everyone has the right microphones and earphones.

Thirty -five seconds to ensure that the props are in place and are tightly secured.

While you are at home to watch the introductory videos that are known as postcards, dozens of people swarm the stage and use the scene for whatever comes.

“We call it the Formula 1 tire change,” says Richard van Rouwendaal, the friendly Dutch theater manager who makes it all work.

“Every person in the crew can only do one thing. You run on stage with one light bulb or one prop. You always walk on the same line. If you go out of the race, you will touch someone.

“It looks a bit like skating.”

The stage team starts to rehearse their “F1 Tyre Change” for weeks before the participants even arrive.

Each country sends detailed plans of their staging, and Eurovision hires stand-ins to play the acts (in Liverpool 2023 they were students of the Local Performing Arts School), while Podiumhands start to shave an accurate seconds of the chat.

“We have about two weeks,” says Van Rouwendaal, who is normally located in Utrecht, but is in Basel for this year’s competition.

“My company is about 13 Dutch people and 30 local boys and girls, who rock in Switzerland.

“In those two weeks I have to find out who is suitable for every job. Someone is good at running, someone is good at lifting, someone is good at organizing the backstage area. It’s a bit like you are good at Tetris because you have to set everything up in a small space, in the perfect way.”

As soon as a song ends, the team is ready to roll.

In addition to the Stage Hands, there are people who are responsible for positioning lights and setting pyrotechnics; And 10 cleaners who sweep the stage with pugs and vacuum cleaners between each version.

“My cleaners are just as important as the stage team. You need a clean stage for the dancers – but also, if there is a overhead shot of someone lying, you don’t want to see shoe prints on the floor.”

The attention to detail is clinical. Backstage, each executor has its own microphone stand, set at the right height and angle, to ensure that every version camera is perfect.

“Sometimes the delegation will say that the artist wants to wear another shoe for the grand finale,” says Van Rouwenaal. “But if that happens, the microphone standard is at the wrong height, so we have a problem!”

SRG / SSR

SRG / SSRHowever, spontaneously changing shoes is not the worst problem that he is confronted with. At the 2022 competition in Turin, the stage 10m (33ft) was higher than the Backstage area.

As a result, they pushed heavy props – including a mechanical bull – a steep slope between each act.

“We were exhausted every night,” he recalls. “This year is better. We even have an extra backstage tent where we prepare the props.”

Getty images

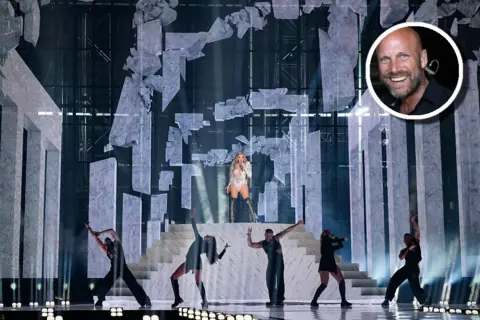

Getty imagesRackisites are a large part of Eurovision. The tradition started on the second game once in 1957, when the German Margot Hielscher was part of her song Phone In (you guessed it) a telephone.

In the intervening decades, the staging has become increasingly extensive. In 2014, Mariya Yaremchuk in Ukraine caught one of her dancers in a giant hamster wheel, while Romania brought a literal cannon in 2017.

This year we have disco balls, space shoppers, a magical food blender, a Swedish sauna and, for the UK, a fallen chandelier.

“It is actually a major logistics effort to get all the props organized,” says Damaris Travel, deputy production head for this year’s competition.

“It is all organized in a sort of circle. The (props) come from the left on stage and are then removed to the right.

“Backstage, the props that have been used, are pushed back to the back of the queue, and so on. It’s all in the planning.”

During the show there are several secret passages and “smuggling routes” to get prop nows in and out of vision, especially when a performance requires halfway through new elements.

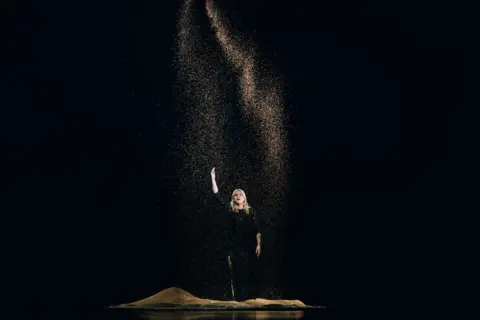

Road your mind back, if you want, to Sam Ryder’s performance for the UK during the 2022 match in Italy.

There he was, only on stage, falsetto notes from his spangly jumpsuit from the conception, when suddenly an electric guitar appeared from the sky and landed in his hands.

And guess who said it there? Richard van Rouwenaal.

“I am a magician,” he laughs. “No, no, no … that was a collaboration between the camera director, the British delegation and the stage team.”

In other words, Richard popped up the stage, guitar in his hand, while the director cuts a wide shot and hide his presence from viewers at home.

“It is choreographed to the nearest millimeter,” he says. “We are not invisible, but we must be invisible.”

Reuters

ReutersWhat if things go wrong?

There are Certain Tricks The Audience Will Never Notice, Van Rouwendaal Reveeals.

If he announces “Stage not clear” in his headset, the director can buy time by showing an extended shot from the public.

In the case of a larger incident – “a camera can break, a plug can fall” – they cut to a presenter in the green room, which can fill for a few minutes.

In the control room, a tape of the rehearsal of the dress in synchronization with the live show plays, so that directors can switch to preceding images recorded in the case of something like a stage invasion or a malfunctioning microphone.

However, a visual glitch is not enough to activate the backup tape, as Zoë Më van Switzerland discovered on the first semifinal on Tuesday.

Her version was briefly interrupted when the feed of a camera on stage froze, but producers simply cut into a wide shot until it was determined. (If it had happened in the final, she would have had the opportunity to perform again.)

“There are actually many measures that are taken to ensure that every action can be shown in the best way,” says travel.

“There are people who know the regulations by heart, who played what could happen and what we would do in different situations.

“I will sit next to our product head, and if there is (a situation) where someone has to run, maybe that will be me!”

Sarah Louise was Nett

Sarah Louise was Nett Sarah Louise Bennett

Sarah Louise BennettIt is no surprise to hear that tracing a live three -hour broadcast with thousands of moving parts is incredibly stressful.

This year, organizers have introduced measures to protect the well -being of participants and crew, including rehearsals with closed door, longer breaks between shows and making a “disconnected zone” where cameras are banned.

Nevertheless, it says that she has worked every weekend every weekend, while Van Rouwenaal and his team regularly last 20 hours.

The shifts are so long that the production legend of Eurovision, built a bunker under the stage in 2008, complete with a bank, a “unfortunately under -utilized” PS3 and two (yes, two) espresso machines.

“I don’t have a hidden luxury like Ola. I’m not at that level yet!” Laughs Van Rouwendaal

“But backstage, I have a place with my crew. We have stroopwafels there and last week it was King’s Day in Holland, so I baked pancakes for everyone.

“I try to make it fun. Sometimes we go outside and drink and cheer because we had a great day.

“Yes, we have to be at the top and we have to be sharp as a knife, but having fun together is also very important.”

And if everything goes according to plan, you don’t see them at all this weekend.