Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

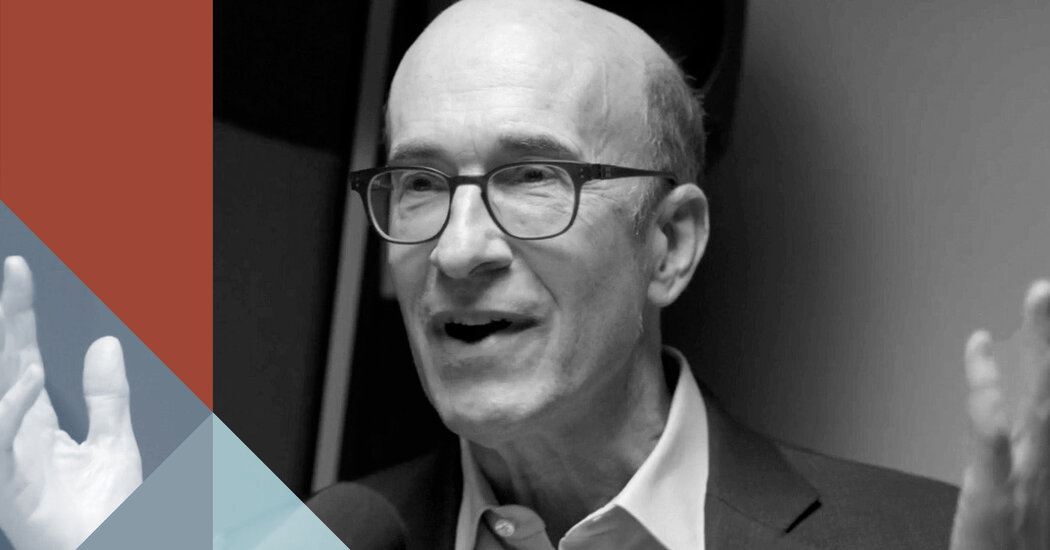

For decades now, America has dominated the global financial system. Our currency is the currency that international trade runs on. Our financial plumbing is the plumbing that basically everybody, to some degree or another, uses. This has been called our “exorbitant privilege.” Because of it, our borrowing costs are lower. Because of it, we know things about the global economy nobody else knows, and have access to information nobody else has access to. We can wrap sanctions around our enemies in a way no one else can. The worry for a long time has been that the world will slip out of this system. There have been challengers. Japan in the ’80s, the E.U. in the 2000s, and now China. But no one has really come anywhere near dislodging it. The Trump administration has had a much more complicated relationship with this, to say the least. If a country tells me, Sir, we like you very much, but we’re going to no longer adhere to being in the reserve currency. We’re not going to salute the dollar anymore. I’ll say that’s O.K. They’ve come to see dollar dominance as a burden we bear on behalf of the rest of the world, and a burden they should be paying more for the privilege of using. You’re going to pay a 100 percent tariff on everything you sell into the United States. And we love your product. I hope you sell a lot of it into the United States, but you’re going to pay 100 percent tariff. Ken Rogoff is the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. He’s a professor of economics at Harvard, and he has a new book coming out, very well timed — it drops on May 6 — which is a history of dollar dominance and a warning that the rest of the world was already beginning to look for exits from it. But now the Trump administration has taken the stress that system was under and begun to put true cracks in it. As always, my email ezrakleinshow@nytimes.com. Ken Rogoff, welcome to the show. Thank you for having me, Ezra. So I want to get at the basics of how the dollar works in the international financial system. We sell dollars to other countries. Other countries buy them. Why so the most important thing is the English analogy. It’s something everyone understands. Partly they know what it is and partly they like it. It’s something they know and trust there. I think 150 plus currencies in the world. And just imagine two people trying to communicate with two currencies they never saw. And let’s just deal in dollars. So that’s a big part of it. It’s like a common language. How did we build that trust. Part of how we built the trust early was the dollar was as good as gold and used to be your dollar bill that you have in your pocket actually said how much it was worth in gold. And you could take it to various places, the bank, banks and get gold for it. And that actually continued for countries until just over 50 years ago. And then we moved to it not being based on gold, it being based on trust in the United States and how we would manage the dollar. Well, we did, but we didn’t tell anyone we were going to do that, and they weren’t very happy about it. I mean, they were holding dollars because they were good as gold and they literally meant gold. And when President Nixon in the early 1971 decided, I don’t want to do that anymore, it was just a shock. It was actually, I think, the biggest shock until recently, but something you often run into when you start trying to study this or pepper conversations about it, is the intensity of the demand for dollar backed assets. And one of things other countries don’t have is the depth of the assets we have to sell. And so it’s not just that the dollar and dollar backed assets like treasuries are. I think, though I like the way you put it, are basically the lingua Franca of international finance. It’s also there’s enough of them to go around. So there’s just not as much liquidity in German currency. Liquidity is an important word. And it means if you want to sell it, do you have to pay a big discount. That if you want to sell your house, you can sell it, but it’s not necessarily something you can sell quickly. So you you’re I don’t know from India and you bought a Treasury bill. You can sell it to anyone in the world. They know what it is. There’s a price, usually not a very big discount from whatever the market price is. Their currency is the rupiah. If you wanted to sell your rupiah abroad, you’d pay a big discount. So deep financial markets rule of law. There are other things open to trade because you can get your money in and out. We’ve had a very open, very open system. I want to be careful, though, about just saying the more we print, the more the demand for it. Nothing could be further from the truth. I mean, actually, as we have more and more debt, the interest rate we pay actually goes up after a while. So there’s a trade off, but we nevertheless we pay a lower interest rate than we would if we were another country trying to do the same thing. So this moves us a bit into the question of what we get for this dominance. Why do we want other countries to buy dollars. It’s free money to us. So when they literally are buying currency, which like the dollar bills in your pocket, that doesn’t pay any interest, and in a way they’re making an interest free loan to us. And there’s the different estimates of how much is abroad. But it’s at least $1 trillion is held abroad. Interest free loan. Much more important is that when they make loans to us in dollars, and that’s the Treasury. Could even be your mortgage getting repurchased somehow because it’s in dollars. Historically, it’s paid a lower interest rate. You get a lower interest rate on your mortgage because someone in China likes dollars. What are the estimates of how much lower borrowing costs are. Interest rates are in America because the whole world is working off of our financial system. So a short answer is for the government, half a percent to a percent, the range of the estimates. That doesn’t mean that we’re paying a lower rate than Germany, because we borrow so much more than Germany. Be very careful about that. But given how much we’re borrowing, think, think of half a percent to a percent. Now, I said, what does that matter when you owe 36 going on $37 trillion. That’s real money. Each percent. But it’s not just the government. It’s your mortgage, your car loan. It pushes down interest rates all over those things your mortgage and your car loan. They can get repackaged in some complicated way, pushed out to Germany, to Japan, to someone else. So it’s affecting everything. So tell me about some of the other benefits. I mean, the dollar dominance, it gets called the exorbitant privilege. Your book is so interesting to read in this moment, because it comes from the perspective that this huge privilege America has, that the other countries that the other countries in the world are growing tired of. And the question is, can we maintain it. And then it comes out at this moment when you have administration that is more or less claiming it to be a burden that the other countries in the world are free riding off of and that we need to begin to pull it back. So why to the rest of the world, does this seem like a great benefit for us. Well, so the phrase exorbitant privilege was coined by Valery Giscard d’Estaing And I literally pardon my French. I’m not saying his name correctly, who didn’t like the idea that the US seemed to pay a lower interest rate. He didn’t like the idea that we seem to be able to borrow so much in a crisis, and he didn’t like the idea that his country needed to hold dollars to fix its exchange rate, which they did. And we were able to take that money and invest it in factories in Europe. So it combined a lot of things. It’s used today often just to refer to how cheaply, you can borrow if you go. During the pandemic, we borrowed twice as much as most other countries were borrowing, but just everybody else looking at Uc was still thinking, Wow, we wish we could do that. And we were able to do it because, for starters, our debt was very low at the beginning and also the interest rate just wasn’t suddenly going up. So they look at it. And when these crises happen, they’re trying. But we’re able to do so much. And as you lose your privilege. And also your debt gets really high. You find that when you try to do it again. Not so much. That’s really the risk. So that’s definitely one of the benefits of being able to borrow a lot when you really, really need it. So you sometimes hear this described negatively as it’s like the rest of the world or dope dealers to America, that it’s made us addicted to debt because we can do this equilibrium where the rest of the world has made it so much easier for us to borrow, and cheaper for us to borrow. Has that been good for us, or has that, as you’ll sometimes hear from the more austerity focused side of the debate, been a kind of net negative because it allowed us to be, in their view, irresponsible? I mean, it’s purely good for us, but where you have to be careful. For example, in the early 2000, we made it a little too easy to come in here with your money and invest it in ways that the government was backing. We deregulated too fast. It was sucking money in. So we didn’t just have the exorbitant privilege we had. You come here and not a lot of regulation. It’s really cool. And that blew up into the financial crisis. So you want to be careful between everyone loves us because we’re just so wonderful. And everyone loves us because we’re so stupid. So then you get into this other question, which I always find a little bit unintuitive, which is that the heavy use of our dollar worldwide makes the things we buy cheaper and the things we sell literal things more expensive. How does that work. So it’s just not true. So this is just the thing that is believed that is just not true. You just hear it from the Trump administration. But it’s not true. It’s just not true. I think they conflate the stock market and houses and things like that, which are of investments with buying a car. Buying cars is cheaper here than in most countries, just because it’s more competitive and stuff like that. They’re not. They’re not the same thing. A lot of even the economists you’re talking to are saying that, I think are being a little incautious. So it’s really a completely separate issue of what the exchange rate is. There have been times when the dollar is really cheap. Now it’s really high. I mean, it’s gone down, but it’s still really high. The forces that affect exchange rates and prices are complex interaction of demand and supply and tastes and stuff like that. So let me even narrow this down a bit because I am where your position is more than where theirs is, and certainly where your position is on the idea that these things are complex. And one of my critiques of the Trump administration, just in general, role is they want to make complex problems into simple problems. They want to take complex forces that we don’t even really fully know how to track and turn them into one thing that you can grab in your fist and squeeze. But the very specific claim being made repeatedly is that part of why America lost so much of its industrial base, so many of its manufacturing jobs. Is that because of all these financial flows, because we had so much money coming into American assets that our dollar became overvalued, we allowed other countries to keep their currency somewhat down China, and that this led to American exports becoming noncompetitive and the American consumer having an appetite for these newly cheap goods flooding into the country. And so very specifically, the argument is that dollar dominance has been something that has hollowed out our industrial capacity and manufacturing jobs. Do you buy that. It’s ridiculous. I mean, so let me just step back a second. You’re drilling in on this, but forgive me. There’s a certain romanticizing of manufacturing that you hear that you used to hear about agriculture. I’m quite a bit older than you, but back in the 19th century. You looked great, though. Back in the 1970s, you had the same ads where you see the person working on machine line or something. You saw them about farmers. They were constantly showing the farmers. We had to help the farmers. And you know what. Those jobs went away, even though we’re the agricultural powerhouse in the world because everything became mechanized. That’s a lot of what’s going on in manufacturing. What we blame on China, a lot of it has to do with the way of the world. These jobs are going away. It doesn’t matter if we don’t trade with anyone. These jobs aren’t going to exist. And that’s just like a false sale that’s being made about that. It’d it’s been great to have middle class jobs, but that kind of middle class job just isn’t going to be there anymore. And to blame that on the fact that everybody’s using the dollar all over the place, it’s silly. So of course, what is the argument being made for that though. You’re just saying it’s ridiculous. And I’m not even saying you’re wrong, but I want to hear you make the argument you’re arguing against. Why does Stephen Moran, the head of Donald Trump’s council of Economic Advisors, why does he think the dollar strength over time was a contributor or a significant contributor to the hollowing out of our industrial base. He’s a Harvard educated economist. He’s your school. He is indeed. And he’s not anything. He’s very good. Well, first of all if you’re in the Trump administration, you can have an opinion on many things, but you’re not allowed to have an opinion on this. I mean, Trump has this as a religious belief and everyone’s dancing around trying to provide a rationale for it. I would say this same phenomenon of we’re buying more from China or Germany than they’re buying from us is their money is coming in there, we’re investing it. We’re building, stuff, not necessarily factories, but our biotech and medicine and services. And we’re paying less than we would otherwise. We’re getting a lot of benefits from it. And a lot of this has to do with that. The incomes are just really low in China and India and many other places. And if you have openness to trade, you can argue about that. But it’s not because of the dollar. It’s because you have openness to trade. And if the dollar had been 30 percent cheaper for the past 40 years, would that have had, in your view, any effect on manufacturing employment at all. I mean, it might have had some effect. It would affect our prices, probably. It would have affect the prices we have over time. If you push the exchange rate and make it too cheap, you’ll get inflation. Wages would go up faster and eventually it wouldn’t be cheaper. I mean, so the argument you can use your exchange rate to manipulate by making things cheaper fails to see that if your things are cheaper, it’ll eventually things will push up the price to make it equal. Workers can demand more. It’ll still be competitive. The reason China stayed in there so long is keeping their currency cheaper than it would have been otherwise, their currency cheaper, mainly because they had a huge number of people earning zero out in the hinterlands. They were bringing 12 to 15 million people a year into their cities to work. And that supply kept wages down. It kept their prices down. We could be on a gold standard. There’s no dollar to manipulate, and we would have lost our manufacturing through trade like that. And by the way, most of our manufacturing jobs have been lost to automation, not trade. Yeah this is the other side of this argument. I think people actually underrate. And I find the Trump people like JD Vance really shift between very, very quickly. Sometimes you’ll hear JD Vance make arguments about immigration, where he says that because we’ve had so much illegal immigration, we have not done as much automation and increased productivity as fast as we would have without it, which is fine. You can make that argument. I think in some ways, it’s even true. But then on the other side, they’ll make this argument about manufacturing jobs. I mean, I have to say, you’re taking this in a direction that’s so hard for me because I have trouble thinking about anything since you’re trying so hard to think about something sensible when I’m hearing polemics from them, they know what they’re supposed to say, or finding arguments that can hold up for a second on immigration, by the way, I favor having a lot of legal immigration would be a very good idea. It’s certainly the case that when you have illegal immigration, it holds down the wages of low income people. I mean, it’s very hard to be competitive as a construction worker. Certain parts of construction work. Be a housekeeper. Be a child care. It’s absolutely holds. If we didn’t have that, the wages would be higher. I mean, that has an effect. But as far as motivating, motivating us to do automation and what industries is he thinking about exactly that. The immigration over the last few years has been in effect on that. I mean, I’m sure he can find something, but I think it’s a stretch. I think we treat in the American political conversation recently, we treat financial dominance as a fake form of power. A financialized economy is a soft, decadent economy, not the Chinese economy, which really builds things. But historically, if you control the money, you control the world. And there’s real power in having all the financial arteries connect back to your pumping system. The fact that the dollar rules allows us to control the global financial system to a remarkable degree. It’s not just the dollar rules. It’s also that we’re the military power. The combination of those two things gives us the ability in global negotiations for how should the IMF vote the International Monetary fund. How should the networks of transactions between countries go. Who should see the information. We get such privileged access to information, it just all goes through us and everyone hates it. Obviously the Russians and Chinese hate it, but the Europeans hate it. In fact, the Europeans forget the Chinese. They’ve been trying to figure out a way to get away from this. Well, to pick an example, in 1956, when the UK still thought it might come back, remember they had ruled the world. The sun never set on the British Empire, and we were trying to put them down. And there was a crisis. And Egypt. The Suez Crisis. And we said, well, you’re not doing what we want you to do. We’re going to call in your loan. If we do that, I mean, exaggerating a bit, but it just it’s incredible power if you control funding. Of course, sanctions is an obvious thing where we’ve been using that in lieu of military power, which O.K, go for it. We can debate how well that’s worked, but believe me, they don’t like it 10 years ago, we were imposing sanctions on Iran. The Europeans didn’t agree with us. And we said, O.K, you don’t agree with us. Forget about using our banking system, which just destroys them. Everyone has to use the US banking system and you go on and on. So they don’t like the power that it gives us in these subtle ways. And again, as an American, you don’t see it. Oh, I’m making the rules of the game. The game is great. I love everything about it. But if you’re elsewhere, you feel it. So this goes back in a way to this idea that the dollar is something of a service we are selling to the rest of the world, and you’re selling the rest of the world a service, a good. You got to keep your customers happy. Now we’ve kept them happy. We tend to think about this in terms of controlling inflation here and being reliable. But one thing, going back before Donald Trump to the way we’ve been using sanctions and other forms of financial power is increasingly we’ve used it as non-economic leverage, as leverage to get people to do other things that we want them to do to sanction people. We don’t like to give us information that maybe they don’t want to give us. And something that’s there in your book is a way that people were getting tired of this even before Donald Trump. So could you talk a bit about that piece. Like, where were we on the Eve of the Trump administration, and how are people feeling about the way we had changed the leverage that our financial system gives us. So Asia is a big part of the dollar bloc. They hold tons of reserves. That’s trillions and trillions of dollars of reserves are lent to us by Asia. They’re very important to us. China is at the center of that. China is the most important trading country, even more important than the United States for many countries. China had been using the dollar. The technocrats had been telling them for a long time, this is dumb. You shouldn’t be using the dollar and the leaders were like, no, they don’t want to change it. But when the Ukraine, the full scale invasion of Ukraine happened and they saw what we did to Russia, we didn’t just sanction them, we took their central bank’s money. And we’re not calling it a default, but of course it is. We froze over $300 billion. Well, the Chinese, they’re looking at that and they’re also looking at the Russians having difficulty using visa, Mastercard, the credit system, everything using dollars. And they saw that. And can’t change it overnight, but they’ve been taking one step after another. And they’ve also they used to peg their exchange rate and just basically try to make the renminbi that’s their currency fixed against the dollar. Well that’s gone. And that’s also moving people away from holding dollar reserves as much because part of why you’re holding them was to protect against China. Where I saw the biggest problem was not the other countries wanting to change things. Where I saw the biggest problem was inside ourselves Federal Reserve independence, which is the core of stabilizing the dollar and our inflation debt. The view that it’s a free lunch. These, I think, ultimately were going to come to bite us anyway. Say a couple words about why Federal Reserve independence is important here. So O.K, I mentioned that it used to be as good as gold. You didn’t care if the Federal Reserve was independent. You didn’t like what the Federal Reserve was doing. And your Japan, you just take your money and you get gold. You’re happy. Nowadays, there’s nothing standing behind the dollar in its value. I mean, that’s what you ultimately care about. That was the gold standard. What’s standing behind the dollar is the Fed. That’s our central bank is promising not to intentionally inflate too fast and actually to try to average around 2 percent I just have to mention I wrote the first paper on central bank independence 45 years ago when nobody had independent central banks, so I’m biased, of thinking it’s a great idea. It’s a relatively modern invention and it has worked. If you get rid of it, there’s always a temptation. Any president again, Trump is the world’s history. The recent history is crudest president. But what he’s saying he really wants the interest rate to be lower. That’s what he wants. Believe me, Joe Biden wanted the interest rate to be lower. Obama did. And for your younger listeners, who probably most of them younger than me. Nixon was brutal about this. You can actually listen to the Watergate tapes, and he’s cursing the head of the Fed. And that led to the biggest inflation we ever had. I mean, that was a real example of losing Federal Reserve independence. So I think this brings us then maybe to the Trump era. So you have these pressures building up. You have the US weaponizing its financial system in more and more explicit and aggressive ways. You have growing US debt when interest rates are pretty low. That felt not as big of a deal. But then post-pandemic inflation interest rates are a lot higher. So all of a sudden the amount we’re going to be paying on our debt is quite a bit up. Then you have Trump and the MAGA movement returned to office in 2025. What has happened since then. If you were writing your book now, if it had a story, a chapter on the last three ish months, what would that chapter say. I mean, it’s still unfolding, but a short thing is the things I was predicting are happening on steroids. I was predicting this to happen, I think. What is this to have risk high much higher risk of inflation undermining Federal Reserve independence, having decline of the dollar. I think that would have happened under a Harris presidency, but it wouldn’t have happened in three months. It would have happened unfolded over a longer period. There were larger forces. Another way of putting it is Trump didn’t have a strong hand as he thought he had. He thought, we were in just great shape. I can do anything. And we didn’t. But I want to hold there for a second. As a person who appears to be trying to make the Trump administration’s arguments on this podcast. He didn’t think we were in great shape. This is their whole argument that we’re in terrible shape that the dollar was in. He thought the dollar was in good shape. He thought the dollar was in good shape. But he thinks that dollar dominance is bad for us on some level they want to make. I find what they say about this. I understand why you say that steelmanning their arguments is impossible because on the one hand, they want, they want. They say the dollar should be weaker and it should also be the completely unquestioned reserve currency. The Moran, the Moran plant. They want it weaker and stronger at the same time. There’s this thing called the mar-a-lago Accords, goes back to the Plaza Accord of the 1980s, trying to do a parallel. It actually tells China, O.K, we’re going to give you 100 year bonds, and I guess we’re going to pick the interest rate on them, and you’re not going to be able to sell them to anyone, and you’re going to love us. And by the way, that’s what you have to do. We’re going to do that to our friends, our enemies, to everyone. We want the dollar to be dominant. Dominant we want you to supplicate. I mean, needless to say, that’s a recipe for blowing up the global financial system, not for having stability. I’m just giving their contradictions. They say they want to be the reserve currency, but we’re willing to be the reserve currency if we don’t have to pay any interest. You can’t do anything with the money and we’re basically defaulting. It is a partial default. It is a spectacular tackler default. Well, if they do that. It’s a default, which they haven’t done most of these things yet. What they have done as best I can tell or as best I read it is say this their theory of the case is the US financial system and the US global military system are functionally global public goods that we provide at cost to the rest of the world. And you guys are all free riders and you’re going to start paying us. You’re going to start paying more for defense. One of the things Moran said, is it one way they could be in our good graces is just to cut a check to the Treasury, just make a donation to the US government for the privilege of using our defense system or our financial system. But what we are going to start doing is squeezing. We are going to say, and they have told me this directly, we have leverage. We have all this leverage that these idiots like Biden and Obama and Bush were not using. We’ve been taken advantage of in deal after deal forever, and now we’re going to using our leverage. We’re going to start squeezing. And if you want to trade with us, if you want to be on the dollar and you better fucking be on the dollar, you are going to be giving us some kind of better deal than you’re giving us now. Maybe you give us a check. Maybe you give us a better trade deal. Maybe you spend more on defense. Maybe it’s something else. But you better come cut a deal and pay some kind of tribute that you’re not currently paying. Whoever you are, right. Even if you’re an island full of penguins and taking that case at its strongest right now, there’s not a very good global alternative to the dollar. Nobody else is really a good option. But the thing that I see is that even if it worked in the short term, even if everybody comes to us and bends the knee because they don’t want to be driven into a recession, Japan makes a deal with us. The UK makes a deal with US, France makes a deal with us. Brazil makes a deal with us. India makes a deal with us. The Philippines make a deal with us. Vietnam makes some deal with us that the signal we sent to everybody. Is it being on our system is incredibly dangerous for you. Because at any moment we might decide to squeeze your throat, and you’re going to have to give us something. You don’t even understand what it is right now. The terms of the deal are unclear and can change at any time under any administration. And what you create then, is incredible pressure to get the hell off of our system. We can’t do it tomorrow. We can’t do it even in a year. But you can start to do things over five or 10 years. That’s what everybody’s doing. That’s what he’s catalyzing. We’re like I said, I thought this would happen over a long period and he’s making it happen on steroids. So yeah, he’s undermining the rule of law trade. By the way, free trade is one of the core things. Just think about a world where we have 100 percent tariffs and you can’t get your stuff in or out. Well, you’re not going to invest in the United States then. That turns out to be true with a 10 percent tariff to a lesser degree. The fact that our financial system is open. What about our University system. Sucking people in, helping integrate them into our culture, our openness to immigration, all of these things, are being undermined that are soft power. What about soft power. All these things are being undermined that are at the core of the dollar strength. Tell me the story. In terms of things that have affected the dollar and what we’ve seen in the dollar’s value and what we’ve seen in other countries responding, what did they do that was consequential. How would you tell the story, as an economic historian, trying to track what has been what has been important in this period. There are a lot of little pieces that remain to be seen, but the tariffs were just the dumbest thing, the most incompetent thing. If he had just put on tariffs that were 10 percent on everyone, we’d all get hysterical because it’s bad for globalization. It would just not have been a big deal. It’s a tax. Taxes are bad. It raises revenue. You could cut another tax. Economists have studied this for decades. We don’t favor it. But it’s not the end of the world. The problem is this. Let’s make a deal. Totally unpredictable. I have a friend who has a little business importing Italian wines, and she doesn’t have a lot of capital. She needs to charge people in advance. What price is she going to charge at the boat. Takes two months to come. She doesn’t know what’s going to happen. Look at bigger corporations. No one knows what’s going on. Investments freezing up. It’s the whole chaos, which I think you rightly described, as just something he plans. I mean, he wants to make himself everyone have to supplicate to him. And he very good at that. But it’s the he can’t do that to the markets, the market. The only reason and the only reason the markets haven’t fallen more is this belief that other things. He’s historically often been pragmatic. And when he screwed up. He declares that wasn’t my opinion ever, and just changes his mind. And he seems to have a deeper seated view about this and the tariffs. And the way he’s doing it is such a disaster because historically, the president is the person who’s kept this in check. Actually, tariffs are very popular. My mother liked tariffs I would explain. I mean, she knew I was a PhD economist. I said yeah, but it makes the price of everything more expensive. She said. She said Yeah, but I want to protect jobs for American workers. And I think when Trump came in and I say this confidently, having talked to high level people around him, he thought everyone loved Harris. He looked at Bernie Sanders, which, by the way, was pretty similar, a lot nicer person. But when it comes to trade, he was saw himself as mimicking Bernie Sanders. I don’t buy that. Oh the whole NAFTA thing. Oh my. He might not like NAFTA, but Bernie Sanders has never proposed a tariff system like this. Yeah, but what was he. Yeah what was he. Well, I don’t know. The whole Trump has had his views on trade since Japan in the 80s. He didn’t need Bernie Sanders to teach him that. If you go back to what he was saying about Japan, it’s the same thing he’s saying now. He’s I’ll back off of that because I don’t want to go there. But it’s popular. It’s not unpopular. And historically Congress has pushed for tariffs. And I’ve met Congress people and senators over there. They all wanted tariffs. They’d ask me about tariffs. Can we have a tariff to protect our local firm. Wouldn’t that be a good idea. We’d have local jobs. So there are all these different Congress people. They have their own districts, their own pressures, their own donations. And the president stood in the way. And here we have a president leading the way. And so I never, that’s the big story that’s happened. And it isn’t over yet. Again, if he sticks to this, we have a lot longer down to go something. You’re saying that I just want to validate through my own reporting is I’ve talked to a bunch of people who are significant market participants as maybe the way I’ll put it, and they are definitely working off of the idea that in a year, the tariffs are going to be much lower than they are today, not a little bit lower, more stable, not the same. It’s the stability. It’s not just the lower, it’s what are they. They can do business if they know what it is. But if they don’t know what it’s going to be and it depends on which side of bed Donald Trump wakes up on and he’s that’s the problem, the total unpredictability of it. So what has this done specifically to the dollar. People have been people know what is going on in the stock market. It has been very shaky. People can watch that for themselves. What has been the story if I’m following the dollar’s value. So I think it’s a question of competency. People are saying if he’s this bullheaded about this mistake, is this Trump many, many years later, older. Is he the same pragmatist that we thought was there before. What if he isn’t. If you look closely at his tax bill, it’s Trump 1 plus a lot of nutty ideas. And people thought he wouldn’t really do them. Make Social Security, not tax tips, not tax changes in state and local. All these different things. Maybe serious the crypto. Maybe he’s serious about it with if you deregulate too much as a problem, maybe he’s not competent in the British used to have this thing with Liz Truss where she was the prime minister for a nanosecond. And she came out with this policy. She hadn’t really sold, and everybody sold the pound. The interest rates went up. It collapsed. And they called it the moron premium because she just didn’t understand. And people were talking in similar terms about what was going on here. I don’t think it’s just about the tariffs. The tariffs are terrible, but it’s a deeper loss of trust in the governance, the institutions. But most people don’t track just what is happening literally to the dollar’s value, where people are putting their money in other currencies. You do. What has happened to the dollar’s value, what has happened with other currencies? I mean, what are the signs that the world’s relationship to the dollar, the dollar is changing. So the thing, which was just a incredible moment for everybody was when the dollar was going down in value, but long term interest rates were going up. There was a couple within a couple of days after his announcement. The 10 year interest rate, which most people don’t think about, but it is the bellwether of global financial markets. It’s the most important market. It’s the deepest market every year. Car loan, your student loan, everything gets referenced off the 10 year rate, not what the Fed does. Everybody talks about the overnight rate the Fed sets. That’s not it’s the 10 year rate. Everyone looks at that. It’s been going up. And suddenly it jumped half a percent within a very short period. And usually the dollar goes up. The interest rates are higher. I’m going to put more of my money in the US, but no, the interest rate was going higher and the exchange rate was going down. That happens when people are selling, when whoever it was, the Chinese, everyone, there was people pulling out of dollar assets that we were it’s sell America first. Was that is that dangerous. Did that reverse itself. It’s stabilized for the moment because Trump has retreated partly. But I think we have what I thought might have taken 10 or 15 years to happen took place within a week, and we’re never going back. So our exorbitant privilege, our lower borrowing, it’s never going back to what it was. We may have lost 1/4 percent a half a percent, just permanently higher. We can have a recession to bring them down. And when we get into that. But we haven’t I don’t think that bell will ever get unrung. Let’s say in 2029. You have pick your candidate. It’s President. Pete Buttigieg, it’s President Moore, it’s President Gretchen Whitmer. You don’t think it all just reverts now because we said the 10 year rate is the bellwether? I didn’t say the four year rate. It’s the 10 year rate. And so what happens in the next election. What happens in the election after that. And it’s possible. We’ve shown we’re willing to put a gun to everyone’s head and Trump. Many of the things Trump does. Other presidents have thought. Go back to the Watergate tech gate tapes and Nixon, where he recorded all his conversations. He’s very younger. He’s very smart, but he’s devious and he’s throwing those sharp elbows. I think there’s he says somewhere I don’t give a damn about the Italian lira, or something when the Italians were having a problem. So they see they’re looking peeking behind the curtain of what’s going on. It’s Trump’s mind, and it’s particularly unpredictable, but it’s deeper in our DNA, the way social media is, the siloing of what everyone reads and watches and listens to. They’re going to worry. It happened once. Why wouldn’t it happen again. So, Yes, it’s hard to understand what the plan is. And it’s definitely I think we have lost trust in a way. We’re never going to get it back. You say it’s hard to understand what the plan is, but. But let me offer. This is not even a plan, but a frame. Somebody said to me recently that their model of Trump is that he loves to borrow from the future he always has, and his businesses and everything. And that if it works out for him, right. In the good scenario for Donald Trump, what you get are some short term wins. What you get is people without a good option like have to give you something. So you bring the tariff down, have to give you something so they get out of your crosshairs. But in the long term, what you’ve done is spend down advantages. We had privileges, we had low borrowing costs we would have had. And maybe the bill comes due for some future president. Maybe it doesn’t. By the way, he’s making these bills come due pretty fast, but it’s a kind of like pulling it from the future into the present. O.K I mean benefits, it would have been spread out over a long time. We’ll get them all now and then deal with the crisis sooner. I’m actually not someone who thinks Trump’s 100 percent wrong about everything he says, but in this area, I’m just I’m working with you. I’m struggling to think of what the logic would be. Let’s go back to the economy is terrible. I mean, even the person in the low 20 percentile from the bottoms very well off even compared to probably, near the middle of the Italian income distribution or much less the world distribution. We have just taken flight during the 21st century. Europe the economy was the same size as the United States in the mid 90s, even into 2000. There were even and their stock market was worth the same. We have had a period where the world has just looked at us in awe, and to come to the end of that period and everything’s terrible. I mean, it’s very hard to understand and say there are things I need to fix. Income inequality, try to bring back, meaningful jobs and those are fine. But I think most of the solutions to those are domestic policy and things you could do differently. And not kill the goose. That’s that lays the Golden eggs. Your book tracks this. There is this way. If you look at our major competitors during this period, you get a somewhat different view of the US than you get from the domestic political debate. So you track the rise of Japan and say some things that it had been a while since I was not really around for Japan as our big competitor. I was very young for that, and I had not really known that there was a period when their stock market was valued more highly than our stock market. I mean, that seems crazy today. Their stock market was worth more. Actually their housing stock was worth more than Japan’s, about the size of California and its housing. It’s hard to get your head wrapped around this, but its housing stock was worth more than the United States. At one point. They just seemed like the coming thing. And that is that’s what everybody thought. I don’t think people anticipated what problems it would have. And I think had they not made some blunders, which we were lucky they did. And we through some sharp elbows at Japan, I mean that’s a case and that maybe that’s why the mar-a-lago accord hearkens back to when we beat up on Japan. We beat up on them. They gave into it. They made a mistake. They appreciated their currency buy a lot more than they intended to. And I’d say that’s one of the things where I changed my mind over time about just how bad that was. I was the view. Well they had their own internal problems, their crisis. They had a two decade growth crisis starting in the early 90s. And that had happened later. It happened six or seven years later. And I later came around to that’s wrong. The view that, for example, the Chinese think that was a disaster. Japan gave in on that. They will never give in on it, give in on it. And I always thought the Chinese were wrong. Others and I came around to well, we set in motion changes that their society was not ready to handle. They didn’t have a monetary framework, they didn’t have a regulatory framework. And for a while they were doing great. But then but then they weren’t. And so it was a surprise how much I felt I was in Japan as a visiting scholar at the Bank of Japan in the early 1990s. I didn’t know what was going on. None of my thesis friends who were economists, nobody knew what was going on. I’d actually invest. I left the Federal Reserve and invested my small pension into Japanese stock. Seemed like a great idea. And if I had sold, then instead of later. So you can go back to other occasions where we were surprised when Europe, nobody knew it would fall as short as it did nobody in the 2000. This part I was more around for in the 2000. There are all these books about the European future. If you just put out trend lines. I mean, the EU as an economic zone was bigger than the United States and they have fallen way behind us. We’ve had a little luck. So I like to quote this chess player I knew, bent Larsen, one of the great chess players. I played him, I knew him, and he had this saying, I heard him, I was being interviewed and he was asked, well, would you rather be good or lucky. And he thought for a second. I’d rather be good and lucky. And Americans know they’ve been good, but they don’t know they’ve been lucky. And fast forward. I mean, our luck may have run out here, that we’ve had a lot of good turns where the other team was making mistakes and we were — I don’t even want to call it an own goal. like in those shootouts in soccer. This isn’t being unlucky. This is being not good incompetent. Yeah Yeah. No, but we’re unlucky in the policies that the administration. I’m saying that’s not being unlucky. We chose this. It’s being not good. Well it’s true because, I mean, I don’t blame everything on Donald Trump. I blame a lot on us. What would we have done otherwise. I mean, I know you’ve written a wonderful book about a brighter visions for the future, but our political system is stuck on a lot of bad ideas on both sides. And this is us. It isn’t just one person. Everything would just perfect if we didn’t have this one person. It’s much. It’s much deeper in our beliefs about ourselves, where we are a certain rot in our system. I mean, maybe that’s too strong to draw the analogy with Rome, but we can turn it around. We absolutely can. I hope we have great government that does. But we need to turn ourselves around in order to do that. So this gets to something I have been worrying about. You’ve been Warning that America is dead. Situation is unsustainable for many, many years. We’ve gone through periods of how controversial that was. I think more recently, kind of everybody’s been getting more worried about the debt. Interest rates are up are total debt load is very high. Our deficits are quite high. Now you have this huge tax cut coming so you can keep all the tariffs and you can raise some money. But if the tariffs are going to go down. They’re going to be raising less money through them. They don’t at any level pay for the tax cut that is currently being planned. So you could very easily be looking at deficits of like 5 percent to 7 percent And a world where they’re causing financial conflagrations let’s call it there’s pressure on the dollar. There is a trade war with China where certainly one of the weapons China has is a sell off in US treasuries, which could put pressure on that market. I’m not predicting a Trump induced financial crisis, but it doesn’t seem impossible to me that those things could combine in a very dangerous way. Not at all, and I think there’s going I think stepping back because I think this is a fundamental point. So there was this idea, particularly among progressives, but also on the right, that interest rates were just going to keep diving down. So it was never going to be an issue. But actually the difference between having 60 percent debt, which is where we were about 2005 of your income and 121 percent today. It’s a big difference in what you can do. Just if you think stimulus is a good thing, if the debt fairy came along and took the 121 percent down to 60 percent you could knock yourself out doing stimulus. The next in coming years. And Donald Trump is going to hit this because the debt has gotten high. Interest rates have normalized. I think if you look at a long history, you never would have thought they would have stayed so low forever. The dollar’s losing some of its his exorbitant privilege. He’s going to throw around money and it’s going to come to bite us. It’s not the end of the world. It’s a little bit hard to predict this man’s mind, but there are two ways. It can end. I think for the United States defaults, not one of them. We don’t need to do that. One would be inflation. I think the chances we get another inflation similar to the Biden era, one or worse, are very high. Very high. 75 percent in the next. How long. The next 5 to seven years is what I say in my book. I’ve got to make that a little shorter. Thanks to the next three to four years, you would say a better than even chance. Yeah, better than even you have inflation at 8 percent or above. Yeah, that’s absolutely what I’m saying. Because that’s where this is going. But you got to take out Powell. You’re saying the inflation option requires that. Because that is a world in which Trump could appoint somebody who would inflate away our debt by printing money to devalue the debt. He’d need to commandeer the whole system because he only controls one position and the others could vote against it. So it’s pretty stable. There’s an incredible culture at the Fed. The others at the federals are the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Board, and the White. But that’s the worry you’re getting at here. The worry I’m getting is that finds a way to corrupt the Federal Reserve. And he could. The idea that he couldn’t. Of course he could, if he needs to. I think a lot of people don’t appreciate that the Fed’s independence is not in the Constitution. Powell he’s the head of the Federal Reserve. It’s not in the Constitution. If with team Congress and Trump acting together, they could, bring it back into the Treasury. So you’d have to do that. And the Trump administration is talking about a lawsuit in front of trying to bring it up to the Supreme Court, basically saying these independent agencies where Trump can’t easily fire the head of them, it’s unconstitutional. So they could win that lawsuit and then they could borrow however they want. No, absolutely. Powell’s term will end at some point. Yeah I mean, I don’t think that would be enough. I think the. Yeah but depending on who they replace, depending on who they replace him with. But they’re not going to reappoint Powell. They’re not going to reappoint Powell. He would not want to be reappointed. Would be my guess. But they’re not going to reappoint him. But it’s not just that. It’s the whole construct. It’s relatively new. It’s not ancient that we’ve had that it is a creature of Congress. It’s not in the Constitution. It could get knocked out very quickly. But to have the inflation option requires that there is another card he can play, and that’s basically ramming debt down people’s throats. The Japanese have done that. That’s why Japan hasn’t had. Japan has debt twice our size, but they’ve used a, to use a jargon word financial repression, pushing debt, the pension funds, the insurance companies, the banks. Everybody has to hold government debt. And they’ve avoided a financial crisis. But there’s no not enough money to lend around to entrepreneurs, innovators. They’ve gone from being richer than us at the beginning of this to being below the UK, France, Germany. They’ve gone from their roughly 60 percent of our income from having been higher. And it’s partly this financial repression. So he has a couple of cards he can play. None of them are good. So we’ve talked about this history in the past couple of decades where you had very dominant seeming countries or countries that seemed on a very bright trajectory, really running into turbulence. And how they look now is very different from how they looked in Europe’s case two decades ago and Japan’s case four decades ago. And it sounds a bit like you’re saying there’s a very good shot that America could enter one of those periods itself, that our sense that our line only goes up is not. That’s not preordained. We were good and we were lucky. And now we might not be good anymore. And we might not be lucky anymore. And if you’re not good and not lucky for 10 or 15 years, you can really lose a lot of altitude. You can lose a lot of altitude. And I think people don’t understand. I want to come back to this, is that if you just went back 20 years, nobody thought the dollar would control so much of the world as it does. And I want to mention that because it’s not so crazy that things would converge back to that. If they did, we’d pay a higher interest rate on our debt. Not as much as if they didn’t use the dollar at all. I maybe we’d still be first among equals. It will affect our national security. Our ability to use sanctions is a heck of a lot less. If you’re visa and you’re the only credit card you can tell people do this or you can’t use visa. But if there’s American Express and Mastercard. You can’t it’ll affect our information gathering, our intelligence. Modern intelligence is mostly cyber these days. It’s not the James Bond, but somebody sitting with a laptop and a heck of a lot of that was our financial information. And if our national security is weaker, we have to spend more money in other ways. I mean, we’ll regret it, but it’s not an overnight. We’re talking about an inflation crisis. I think this loss of the dollar’s magnitude, the altitude comes down from the altitude. It is it’s a slower burn. We will feel it when that pandemic comes. When that crisis comes, people love us. They don’t love us as much. We try to borrow typically two or three times what everyone else is borrowing. And suddenly, the interest rates are moving up faster than they do now. So if over the next 10 ish years, people are just. They’ve lost trust in the dollar. What do they go to when you think of what is the likeliest scenario 10 or 15 years from now in a bad scenario for the dollar. Is it that China has built financial dominance. Is it that many different currencies are used in slightly higher proportions than now, the multipolar scenario that people talk about. Are we all in Bitcoin. We’re not all going to be on Bitcoin. The multipolar Saturday we lose market share. Think of there’s a natural network externality that makes Amazon giant that made Facebook giant that makes Google search giant. The same thing is true in currency. And a lot of economists have these theories. Well, therefore the dollar is always going to be there. But we live in a political world. It’s not in China’s, Russia’s it’s not in Europe’s interests to have us control everything. They are willing to pay a price in order to not have the dollar have as much power, and they were offering them a golden opportunity. I mean, China is already courting Africa, Asia, South Asia, especially Latin America. Europe is remilitarizing. They’re realizing that, Wow, this is a potential moment for the euro. So I think we lose footprint. I do think Bitcoin is in the mix, the CyberGuy because part of the dollar’s footprint is the non-tax paying underground economy is very much dollarized economy. That’s nobody knows for sure how big that is. My in my work, my estimates 20 percent and 20 percent of the global economy is not paying a lot of it’s not paying taxes. And crypto is very useful there. It’s been a real alternative. Aside from being electronic, you can do things more conveniently. It’s more difficult to trace. So crypto is going to take a part of our market share. It’s doing it. The renminbi is going to take up part of our market share, not in New York but somewhere. And the euro is going to take some of our market share. And we’ll have settled to where we thought we were going to be 20 years ago before we had this period. I just want to come back to something you said about military. Actually, I think it’s important. Basically, Yes. I think a good system would be if everyone had to write a check to us and didn’t build up their military. The trouble is, and I think presidents have faced this over the years, when they do that and it starts to get to be a big check, they want something for it. At the end of the day, we want to control things. We didn’t really want NATO to be calling the shots. And when there are no NATO missions, the Uc is controlling them. We are the boss. We tell people what to do. We want it that way. So you wish they would just pay you a check, but then you find out it’s golden handcuffs at the end of the day. Of course, if they have their own powerful military, that’s a whole other story when we disagree with them. So it sounds a bit like one thing you’re saying is that it has been a view of the Trump administration, that everybody is free riding on the financial military services we provide to the world, and we might persuade them of that and persuade them that they should provide more financial military services to themselves, or at least find another contractor or seller. And we might miss that when it is diminished from where it’s been. Yeah I mean, another way of putting it is everyone wishes they were US. I mean, this is the great power turning on itself and pulling into retreat. And I think we’re going to wish we hadn’t done it. I think the comedian Dave Chappelle said it very well. I want to wear Nikes. I don’t want to make Nike’s, and it’s going to be a very different world. Always our final question what are three books you’d recommend to the audience. O.K, well, I have a few books to recommend, but I have to start out with my wife’s book, Muppets in Moscow, which I’ve given you as a present about the making of Sesame Street in the 1990s, which she oversaw hundreds of artists, the making of it in Russia, making of it in Russia in original version in Russian, overseeing directors, puppeteers, writers and such. And it’s in a period of tremendous instability. Another book that I think has I just love and people have seen the series but haven’t read the book. It’s “The Queen’s Gambit” by Walter Tevis. It is one of the most perfect books ever written. Kind of asked the question, what if Bobby Fischer, maybe the greatest chess player of all time, was a woman. How would it have played out. And the Netflix series was just majestical and another book would be Walter Isaacson’s Ben Franklin. I just hadn’t known everything about him, and he was the best chess player in the colonies, by the way, which I was a professional chess player and he printed money. He was very technical. He figured it out. But you know what an amazing person. And I think an amazing book. Ken Rogoff, Thank you very much. Thank you.