Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Senior International Correspondent

Reuters

ReutersAfter 40 years, killed with 40,000 people, and without securing a Kurdish home country, the forbidden Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK, ends his war against the Turkish state.

This indicates the end of one of the longest conflicts in the world – a historic moment for Turkey, the Kurdish minority and neighboring countries in which the conflict is spilled.

A spokesperson for the ruling party of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said it was an important step in the direction of a country without terror.

But what does the PKK get for disarmament and dissolution? So far, the government has not made any promises – at least publicly.

Necmettin Bilmez, 65, a driver, was skeptical about what could follow.

“They (the government) have misled us for thousands of years,” he said.

“If I get an ID card in my pocket that I am Kurdish, I will believe that everything will be resolved. Otherwise I don’t believe in this.”

Sitting in the neighborhood on a small woven stool, had Mehmet, European Championship, 80, a different image.

“This came late,” he said.

“I wish it had happened ten years ago. But still everyone from every side who will stop this bloodshed, I greet them,” he said, tilted the top of his flat cap.

“This conflict is brother about brother. The one who dies in the mountains (PKK) belongs to us and the soldier (of the government) belongs to us.

“We all lose, Turks and Kurds.”

He wants an amnesty for PKK hunters – like many here – and the release of prisoners of Kurdish politicians.

“If that all happens, it will be a wonderful peace,” he said.

In this majority Kurdish city in Southeast – Turkey – the de facto Kurdish capital – we found a muted response to the announcement of PKK.

The city has been signed and reformed by the conflict.

Turkish troops and the PKK fought in the heart of Diyarbakir in 2015. You can still see the rubble of buildings that are flattened by the Turkish army.

Many local people told us that they welcomed peace, or the idea of it, and no longer wanted to kill – Turkish or Kurdish.

“Nobody has achieved anything,” said Ibrahim Nazlican, 63, drinking tea in the shadow of the towering city walls, which have guarded Diyarbakir since Roman times.

“There is nothing but damage and loss, on this side and on that side. There are no winners.”

The conflict varied from the mountains of Noord -Irak – which in recent years has become PKK headquarters – to the largest cities in Turkey.

In addition to a football stadium in Istanbul in 2016, a PKK branch carried out a double bombing in which 38 police officers and 8 civilians were killed. Many Kurds and Turks hope that this is the end of a dark chapter, which has claimed 40,000 lives

Getty images

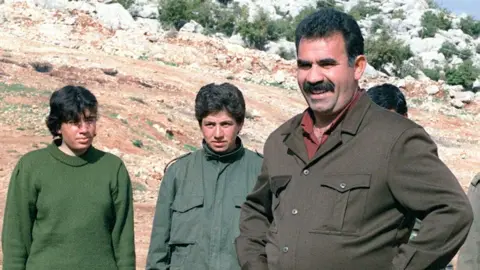

Getty imagesThe PKK decision imposed his arms, followed a call in February by his prison leader, Abdullah Ocalan, who said there was “no alternative to democracy”.

For now, the 76-year-old remains in his cell in an island prison of Istanbul, where he has been held since 1999.

For his supporters, he remains a heroic figure who has put their business on a global agenda. They want him to be released.

Menice, 47, is among them. She insisted that his release was the key to a new dawn for the Kurds, which are good for a maximum of 20% of the Turkish population.

“We want peace, but if our leader is not free, we will never be free,” she said.

“If he is free, we will all be free and the Kurdish problem will be solved.”

BBC/OZGU Arslan

BBC/OZGU ArslanShe is surrounded by family photos of loved ones who died to fight for the PKK – which is classified by Turkey, the UK, the US and the EU as a terrorist organization.

She has lost five family members, including her brother and her eldest son Zindan.

At the age of 17 he joined the PKK and was dead at the age of 25, killed in a Turkish air raid three years ago.

The eyes of Menice fill with tears while telling us how he used to help her with the household work.

His path may have been mapped from birth.

“We called him Zindan (which means cell) because his father was in prison when he was born,” she told us.

A large photo hangs on the wall, shows Zindan next to his brother, Berxwendan, who followed his footsteps “the mountain” to the PKK, when he reached the age of 17.

BERXWENDEN is now 23. His mother did not know if he was alive or was dead until he sent his family a picture of himself during Ramadan in March.

Menice hopes that her surviving son can now come back.

“I hope that Bxwendan and his friends will come home. As a mother I want peace. Let no murders are. Has there not been enough for everyone?”

But does she believe that there can be peace between Turkey and the Kurds?

“I believe in ourselves, in Ocalan and our nation (the Kurds),” she said firmly.

“The enemy (the Turkish authorities) forced us not to believe in them.”

However, pro-Kurdish political parties have some leverage.

Erdogan needs their support to enable him to run a third term as president in elections in 2028.

For its part, the PKK has been struck hard in recent years by the Turkish army with leaders and hunters who have been hunted on drone war.

And regional change, in Iran and Syria, means that the militant group and its affiliated companies have less freedom to operate.

Both parties now have their reasons to close a deal. That can be a reason for hope.