Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

BBC“This one,” says Dr. Anas al-Hourani, “come from a mixed mass grave.”

The head of the newly opened Syrian identification center is next to two tables, covered with thigh. There are 32 of the human thighs on every laminated white tablecloth. They are neatly aligned and numbered.

Sorting is the first task for this new link in the long chain from crime to justice in Syria. A “mixed mass grave” means that corpses were thrown on someone else.

The chances are that these bones belong to some of the hundreds of thousands that are believed to have been killed by the regimes of deposited President Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, who together ruled Syria for more than five decades.

If so, says Dr. Al-Hourani, they belonged to the more recent victims: they died no more than a year ago.

Dr. Al-Hourani is a forensic odontologist: teeth can tell you so much more about a body, he says, at least when it comes to identifying who the person was.

But with a thigh, the laboratory workers in the basement of this squat can start gray office building in Damascus with the task: they can have the length, gender, age, what kind of work they had; They might also see if the victim has been tortured.

The gold standard for identification is of course DNA analysis. But, he says, there is only one DNA test center in Syria. Many were destroyed during the civil war of the country. And “Due to sanctions, many of the predecessor chemicals that we need for the tests are currently not available”.

They are also informed that “parts of the instruments can be used for aviation and therefore for military purposes”. In other words, they can be considered “double use”, and so banned by many Western countries from export to Syria.

Add to that, the costs: $ 250 (£ 187) for a single test. And, says Dr. Al-Hourani: “In a mixed mass grave you have to do about 20 tests to collect all parts of one body”. The Lab is entirely relating to financing the Red Cross international committee.

The new government of Islamic Rebellen-Rulers says that what they call “transitional law” is one of their priorities.

Many Syrians who have lost family members and have lost all the traces of them, have told the BBC that they are not impressed and frustrated: they want to see more trouble of the people who finally Bashar al-Assad from Power Last December after 13 years of war.

During those long years of conflict, hundreds of thousands were killed and millions were displaced. And according to one estimate, more than 130,000 people were violently disappeared.

In the current speed it can take months to identify only one victim of a mixed mass grave. “This,” says Dr. Al-Hourani, “will be the work of many, many years.”

Eleven of those “mixed mass graves” are thrown around a beautiful, bare hilltop outside of Damascus. The BBC are the first international media to see this site. The graves are now clearly visible. In the years since they were dug, their surface has sunk into the dry, stony earth.

Accompanied by Hussein Alawi Al-Manfi, or Abu Ali, as he also calls himself. He was a driver in the Syrian army. “My charge,” says Abu Ali, “were human bodies.”

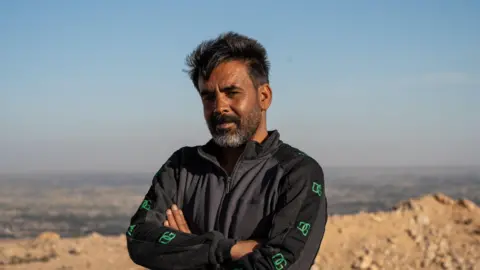

This compact man with a salt and pepper beard was traced thanks to the tireless research work by Mouaz Mustafa, the Syrian-American executive director of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, a interest group based in the US. He had persuaded Abu Ali to join us, witnessing what Mouaz calls “the worst crimes of the 21st century”.

Abu Ali transported trucks of corpses to several locations for more than 10 years. At this location he arrived on average twice a week at the start of the demonstrations and then the war, between 2011 and 2013.

The routine was always the same. He went to a military or safety installation. “I had a 16 m trailer (52ft). It was not always filled on the edge. But I think, I think, on average 150 to 200 bodies in each load.”

From his charge he says he is convinced that they were citizens. Their bodies were “mutilated and tortured”. The only identification he could see were numbers written on the cadaver or held on to the chest or forehead. The figures identified where they had died.

There were many, he said, from “215” – a notorious military intelligence detention center in Damascus known as “Branch 215”. It is a place where we will visit again in this story.

The trailer of Abu Ali did not have a hydraulic lift to give and dump his load. When he withdrew to a trench, soldiers pulled the bodies in the hole one after the other. Then a front loader tractor would “flatten them, compress them, fill the grave.”

Three men with weathered faces from a neighboring village have arrived. They confirm the story of the regular visits of military trucks to this remote place.

And as for the man behind the wheel: how could he do this for week after week, year after year? What did he tell himself every time he climbed in his taxi?

Abu Ali says he has learned to be a stupid servant of the state. “You can’t say anything good or bad.”

While the soldiers threw the corpses in the freshly excavated wells, “I would just walk away and look at the stars. Or look down at Damascus.”

Damascus is where Malak Aoude recently returned, after years as a refugee in Turkey. Syria may be freed from the chokehold of the dictatorship of the Assads. Malak is still a life sentence.

For the past 13 years she has been locked up in a daily routine of pain and desire. It was 2012, a year after some people in Syria dare to protest against their president, that her two boys had disappeared.

Mohammed was still a teenager when he was conscript in the army of Assad, while the demonstrations spread and led the deadly performance of the regime to a full war.

He hated what he saw, says his mother. Mohammed started to go into hiding and even went on the demos himself. But he was traced.

“They broke his arms and hit his back,” says his mother. “He spent three days unconscious in the hospital.”

Mohammed went again Awol. “I miss him,” says Malak. “But I hid him.”

In May 2012, 19-year-old Mohammed Luck sustained. He was caught with a group of friends. They were shot. Malak says there was no formal report. But she has always assumed that he was murdered.

Six months later, Mohammed’s younger brother Maher was towed by school officers. It was Maher’s second arrest. He went to the protests in 2011, 14 years old. That had led to his first arrest. When he was rented out of detention a month later, he was in his underwear, covered, his mother says in cigarette burns, wounds and lice. “He was terrified.”

Malak thinks Maher disappeared from school in 2012 because the authorities had discovered that she had hidden his older brother. Now, for the first time in 13 years, Malak returns to that school, desperately to get an idea of what happened to Maher.

The new Headteacher produces a pair of battered red grandbooks. Malak follows the rows of names with her finger and then finds her son’s name. December 2012, the record states: Maher is excluded from school because he is not in favor of appearing two weeks before lessons.

There is no explanation that it is the state that has disappeared him. However, there is something else: a folder with Maher’s school records has been found. The cover is decorated with a photo of a wise Bashar al-Assad, which is careful in the distance. Malak takes a pen from the desk of the buyer and scribbles over the photo. Six months ago that gesture could have been deadly.

For years, the only leftovers that Malak had to cling, were two men who say they saw Maher in “Branch 215” – the same military detention center that produced so much corpses for Abu Ali to transport.

One of the witnesses told Malak that her boy had told him something about his parents that, his mother says, only he could have known. It was definitely he. “He asked this man to tell me that he was doing well.” Malak waves and leaks tears, puts a torn tissue in the corners of her eyes.

For Malak, like so many Syrians, the fall of Assad was not only a day of joy, but of hope. “I thought there was a 90% chance that Maher would run out of prison. I was waiting for him.”

But she was not even able to find her son’s name on the prison lists. And so the knock of pain stays through her. “I feel lost and confused,” she says.

Her own younger brother, Mahmoud, was killed by a tank that shoots civilians in 2013.

“At least he had a funeral.”