Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC India YouTube team

Illustration by Puneet Kumar

Illustration by Puneet KumarAt a time when the participation of women in the film industry was rejected, a young woman dared to dream differently.

In the 1920s, PK Rosy pre-independence India became the first female lead in the Malayalam-language cinema, in what is now the southern state of Kerala.

She played in a film called Vigathakumaran, or The Lost Child, in the 1920s. But instead of being remembered as a pioneer, her story was buried – deleted by caste discrimination and social recoil.

Rosy belonged to a community with a lower caste and was confronted with intense criticism for portraying a woman from the higher caste in Vigathakumaran.

Almost a hundred years later there is no surviving proof of Rosy’s role. The reel of the film was destroyed and the cast and crew all died.

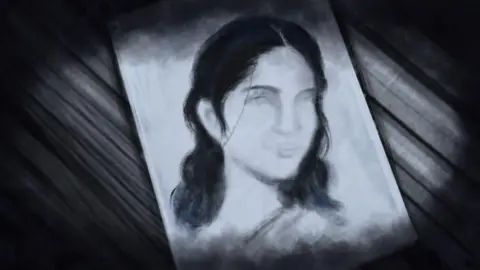

Only a few photos of the movie from one PRESS REPORT Dated October 1930 Survive, together with a non-rewarded black and white photo that is popularized by local newspapers as Rosy’s only portrait.

Even one Google Doodle celebrates its 120th birthday used an illustration similar to the woman in the photo. But Rosy’s cousin and others who have investigated her life told the BBC that they could not definitively say that she is in the photo.

PK Rosy was born as Rajamma in the early 1900s in the former Kingdom Travancore, now Kerala.

She belonged to a family of Grassnijders from the Pulalaya community, part of the Dalits, which are at the bottom of the hard caste hierarchy of India and are historically suppressed.

“People from the Pulalaya community were considered slave labor and auctioned with land,” says Malavika Binny, a professor in history at Kannur University.

“They were considered the ‘lowest’. They were melted, raped, tied to trees and set on fire for so -called violations,” she adds.

Despite the terrible social challenges, Rosy chose to dream differently.

Illustration by Puneet Kumar

Illustration by Puneet KumarShe was supported by her uncle, who was a theater artist herself, and with his help, Rosy entered the field of entertainment.

“There are few available facts about Rosy’s life, but it is known that she was popular because of her performances in local plays,” says Vinu Abraham, the author of the Lost Heroin, a novel based on Rosy’s Life.

Although her acting skills deserved admiration, it was rare that a Dalit woman acted at that time.

“She was probably aware of the fact that this was a new arena and making herself visible was important,” says Prof Binny.

She soon became a well -known figure in local theater circles and her talent caught the attention of director JC Daniel, who was then looking for a protagonist for his film – a character called Sarojini.

Daniel was aware of Rosy’s caste identity and chose to throw her into the role.

“She got five rupees a day for 10 days of filming,” said Mr. Abraham. “This was a considerable amount in the 1920s.”

On the day of the film’s premiere, Rosy and her family were allowed to attend the screening.

They were stopped because they were dalits, says Rosy’s cousin Biju Govindan.

And so a series of events started that pushed Rosy out of the public eye and her house.

“The crowd that came to watch the film was provoked by two things: Rosy played a woman from the higher caste and the hero who picked a flower from her hair and kissed it in one scene,” said Mr. Abraham.

“They started throwing stones at the screen and Daniel chased away,” he added.

There are several reports of the extent of the damage to the theater, but what is clear is the toll that the incident has taken on both Rosy and Daniel.

Poster of the film Vigathakumumaran

Poster of the film VigathakumumaranDaniel had spent a lot of money to set up a studio and collect resources to produce the film, and was hit hard. Faced with immense social and financial pressure, the director, who is now generally considered the father of Malayalam Cinema, never made another film.

Rosy fled her hometown after an angry crowd set her house on fire.

She broke all ties with her family to prevent her from being recognized and never spoke publicly about her past. She rebuilt her life by marrying a man from the higher caste and took the name Rajammal.

She lived for the rest of her life in darkness in the city of Nagercoil in Tamil Nadu, says Mr. Abraham.

Her children refused to accept that PK Rosy, the Dalit actor, their mother was, says Rosy’s cousin, Mr. Govindan.

“Her children were born with the identity of a Kesavan Pillai in the higher caste. They chose their father’s seed above their mother’s womb,” he says.

“We, her family, are part of the Dalit identity of PK Rosy before the release of the film,” he said.

“In the space they inhabit, Caste limits them to accept their Dalit heritage. That is their reality and our family has no place in it.”

In 2013, A TV canal from Malayalam Traced Rosy’s daughter Padma, who lived somewhere in financial tension in Tamil Nadu. She told them that she didn’t know much about her mother’s life for her marriage, but that she did not act afterwards.

The BBC made attempts to contact Rosy’s children, but their relatives said they were not at ease with the attention.

Prof Binny says that the erasing of Rosy’s inheritance shows how deep caste -based trauma can run.

“It can be so intense that it forms or defines the rest of a person’s life,” she says, adding that she is happy that Rosy finally found a safe space.

In recent years, Dalit filmmakers and activists have tried to reclaim Rosy’s inheritance. Influential Tamil director Pa Ranjith has launched an annual film festival in her name that is celebrating Dalit Cinema. A Movie society And Foundation were also established.

But there is still a spooky feeling that although Rosy was eventually saved, it was at the expense of her passion and identity.

“Rosy gave priority to survival above art and as a result never tried to speak publicly or to recover her lost identity. That is not her failure – it is that of society,” says Mr. Govindan.

Follow BBC News India up Instagram” YouTube, Twitter And Facebook.