Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC News, Mumbai

BBC

BBCTucked away in a lane in the southern end of the financial capital of India, Mumbai, is a museum dedicated to the followers of one of the world’s oldest religions, Zoroastrianism.

The Framji Dadabhoy Alpaiwalla Museum documents the history and legacy of the old Parsi community – a small ethnic group that quickly decreases and lives largely in India.

Now estimated at only 50,000 to 60,000, it is assumed that the Parsis are descendants of Persians who were fled by Islamic rulers that were fled centuries ago.

Despite their important contributions to the economic and cultural material of India, a lot about the Parsi community remains little known to the regular population and the wider world.

“The newly renovated museum hopes to shake off part of this uncertainty by inviting people to explore the history, culture and traditions of the Parsi community by the rare historical artifacts that are shown,” says Kerman Fatakia, curator of the museum.

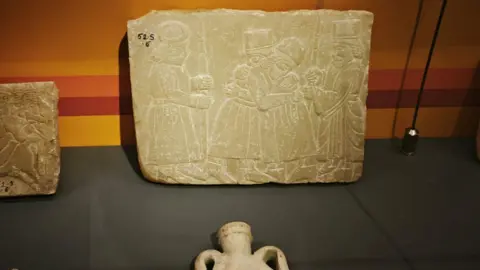

Some of these include nuclear bricks, terracotta pots, coins and other objects from places such as Babylon, Mesopotamia, Susa and Iran and are dated to 4000-5000 BC.

These are places where once Zoroastrian Iranian kings ruled, such as the Achaemenian, Parthian and Sasanian dynasties.

There are also artifacts from Yazd, a city in Central Iran that was once a bare desert and the place where many Zoroastrians settled after fleeing other regions of Iran after the Arab invasion in the 7th century BC.

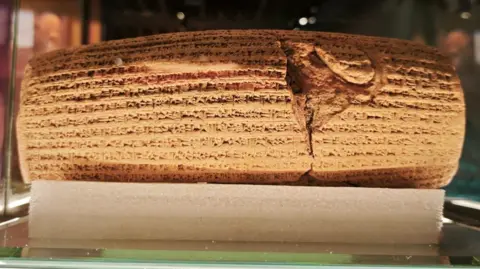

One of the remarkable artifacts that can be seen is a replica of a clay cylinder by Cyrus the Great, a Persian king who was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire.

Fatakia says that the clay -cylinder – also known as the “edict of Cyrus” or the “Cyrus -cylinder” – is one of the most important discoveries of the old world. Registered in the cuneiform script, it outlines the rights that Cyrus granted to his subjects in Babylon. Seen everywhere as the first human rights charter, a replica is also shown at the United Nations.

Then there are maps that follow the migration routes of thousands of Iranian Zoroastrians who fled their home country for fear of persecution and traveled to India in the 8th to 10th centuries, and again in the 19th century.

The collection also has furniture, manuscripts, paintings and portraits of prominent parsis – including Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, founder of the iconic Tata group, who owns brands such as Jaguar Land Rover and Tetley Tea.

Another striking section shows artifacts collected by Parsis that became rich in the early 19th -century trade tea, silk, cotton – and especially opium – with China. The exhibitions include traditional Parsi saris that are influenced by designs from China, France and other regions formed by these global trade tires.

Two of the most fascinating exhibitions of the museum are replicas of a tower of silence and a Parsi -fire temple.

The Tower of Silence, or Dakhma, is where Parsis leaves their dead to return to nature – neither buried or cremated. “The replica shows exactly what happens to the body once it has been placed there,” says Fatakia, and notes that access to real towers is limited to a select number.

The life-sized replica of the fire temple is equally fascinating and offers a rare glimpse in a holy space that is typically forbidden for non-parsis. Modeled on a prominent Mumbai temple, contains the holy motifs inspired by the ancient Persian architecture in Iran.

The Alpaiwala Museum, originally founded in 1952 in what was then Bombay, is one of the older institutions of the city. Recently renovated, it has now fallen modern displays with well -captured exhibitions in glasses. Every visitor is offered a tour.

“It’s a small museum, but it’s full of history,” says Fatakia.

“And it is a great place for not only the inhabitants of Mumbai or India to learn more about the Parsi community, but for people from all over the world.”