Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

North -America Correspondent

Macpherson -Family

Macpherson -FamilyWhile 135 cardinals meet in Rome to decide the next pope, questions about the inheritance of the last great will appear about their discussions.

For the Catholic Church, no aspect of the record of Pope Francis is more sensitive or controversial than his treatment of sexual abuse of children by members of the clergy.

Although he is generally acknowledged that he went beyond his predecessors in the recognition of victims and the reforming of the church’s own internal procedures, many survivors do not think that he has gone far enough.

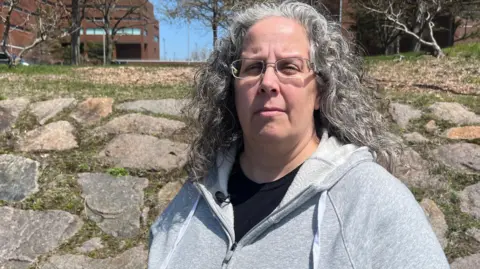

The abuse of Alexa Macpherson by a Catholic priest started around the age of three and went on for six years.

“When I was nine and a half, my father caught him to rap me on the couch of the living room,” she told me when we met on the waterfront of Boston.

“For me it was almost a daily event.”

When discovering the abuse, her father called the police.

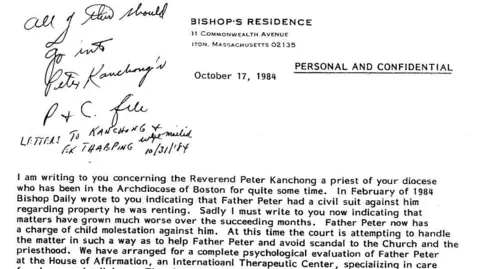

A hearing for a criminal complaint against the priest, Peter Kankong, accused of mistreatment and battery of a minor, was established on August 24, 1984.

But without the family’s knowledge, something extraordinary took place behind the scenes.

The Church – an institution that achieved enormous power in a deep Catholic city – believed that the court stood aside.

“The court tries to handle the case in such a way that Father Peter helps and avoid scandal for the church,” wrote the then Archbishop of Boston, Bernard Law, in a letter that would remain hidden for years.

Thinking about the events of more than four decades ago, Mrs. Macpherson acknowledges that her abuse took place long before Francis became Pope.

But in the same period, due to a series of global scandals that still unfold, the issue of the systemic sexual exploitation of children has become the greatest challenge of the modern church.

It is a challenge that she believes that Pope Francis could not get up because she made it clear when I asked her how she had responded to the news of his death.

“I don’t really feel that I had a lot of response,” she replied.

“And I don’t want to take away the good thing he did, but there is just so much more that the church and the Vatican and the people who can lead can do.”

The letter from 1984 of the Archbishop Bernard Law was addressed to a bishop in Thailand.

In the mention of the accusation of “child abuse” it was written two months after the hearing of Boston, which had indeed closed for the church without a scandal.

Peter Kankong – who originally came from Thailand – was spared from formal criminal charges and was given a probation service of a year on condition that he blended from the Macpherson family and underwent a course of psychological therapy.

The letter from the Archbishop, however, noted that even the church’s own psychological evaluation had established that the accused priest was “not motivated and not responded to therapy” and therefore “should be forced to face the consequences of his actions” among both the civil and the church law.

But instead of acting on that advice, he begged the Thai bishop to immediately remind Peter Kankong of his diocese in Thailand, and for the second time mentioned the risk of “serious scandal” if he stayed in the US.

Although press releases from the time suggest that the ecclesiastical authorities in Thailand agreed to take him back, Peter Kankong ignored the recall and found work in the Boston area in a facility for adults with learning disabilities.

In 2002, more than 18 years after Mrs. Macpherson’s father called the police for the first time, the letter from the Archbishop was made public.

In a milestone statement, it was one of the thousands of pages with documents that a court in Boston ordered the Catholic Church to be released.

Catholic Church

Catholic ChurchA local newspaper, the Boston Globe, began to seriously challenge the power of the institution in the city by placing the stories of victims on the front pages.

Soon hundreds had emerged and their lawyers fought in court to praise for decades of internal archives with regard to the sexual abuse of children.

The church had tried to claim that the protection of the first amendment to freedom of religion gave the right to keep those files secret.

The order to switch them off led to a turning point.

Peter Kankong was contacted at the time and denied the allegations.

‘Do you have proof? Do you have witnesses? ‘ He told the Boston Globe, who still found him in the area.

However, Mrs. Macpherson was one of the more than 500 victims who won a civil case of $ 85 million for the abuse they had suffered by dozens of priests.

The internal files showed that the Archbishop Act had time and again treated his knowledge of abuse in the same way as he had tried to deal with Peter Kankong – by simply moving priests to new parishes.

After the settlement, and then a cardinal, Bernard Law resigned from his position in Boston and moved to Rome.

For the survivors, the feeling of the impunity of the church was further aggravated when he was given the honor of a seven -year position as the Arch priest of the Basilica Di Santa Maria Maggiore, the same building where Pope Francis is now buried.

Getty images

Getty imagesMany insiders of the church describe Francis with go beyond its predecessors to tackle the issue of abuse.

In 2019 he called on more than a hundred bishops to Rome for a conference on the crisis.

In the abuse of children, he told them: “We see the hand of evil.”

The conference led to a revision of the church law on “pontifical confidentiality”, which required cooperation with the civil courts if necessary in the event of abuse.

However, the change does not forces the disclosure of all information regarding child abuse, only their disclosure in specific cases when formally requested by a legitimate authority.

Likewise, a new law stops that requires accusations are referred.

The lawyer of Mrs. Macpherson, Mitchell Garabedian, a man who is depicted in the blockbuster -stichter van Hollywood about the Boston abuse scandal, told me that there are enough ways in which the church continues to perform confidentiality.

“We have to litigate in court to get documents, nothing has really changed,” he said.

His legal victory from 2002 may have been a determining moment, followed by an avalanche of such cases in dozens of countries, but he does not doubt that knowledge of misconduct remains hidden in churches around the world.

“Although he did some things, it is not enough,” Mrs. Macpherson told me when I asked about this issue for her assessment of Pope Francis’s record.

Getty images

Getty imagesShe wants the church to reveal everything what it knows.

“One of the biggest things is turning predatory priests and the people who have covered it and holding them responsible in a normal court and do not protect them and hide them longer.”

Looking at the endless news of the Pope’s funeral and the preparations for the appointment of his successor has been painful for her.

“It is the abuse that is celebrated in a certain way,” she told me, “because the cover-ups are still there, they are protected behind the Vatican walls and their canon laws.”

It is news item that she has found difficult to escape because of the constant faith of her mother in the Catholic Church.

“It is all I have heard on the news, and she is obsessed with viewing this, and so I am just closed and flooded with it.”

Now 85 years old, Peter Kankong has never been convicted of a violation.

He is also not stripped of his priesthood, although he is prevented from holding a formal position in the diocese of Boston.

The own published list of the church of accused clergymen marks his case as “not yet resolved” without definitive decision of guilt or innocence, and simply notes that he is “AWOL” – absent without leave.

“I have tried to discover him for years and that is because he can only be discovered where he was dedicated, that was in Thailand, or by the Vatican,” said Mrs. Macpherson.

She points out that the church has taken the trouble to change the name of the parish where it was abused – is she in order, she believes, to try again after what took place there.

The BBC asked the diocese of Boston for his views on the legacy of Pope Francis and for a response to claims that the Catholic Church maintains a secret of confidentiality about its own internal archives.

We have not received an answer to those questions.

We also asked if the current Archbishop could do everything to help victims remove a priest from the priesthood.

We were referred to the Vatican.

While the Catholic Church is now choosing a new pope, Mrs. Macpherson has little hope for more extensive reform.

“You say you want to move forward. You say you want to bring people back in the fold,” she said.

“But you can do that impossible until you really recognize those sins, and you keep those people responsible.”